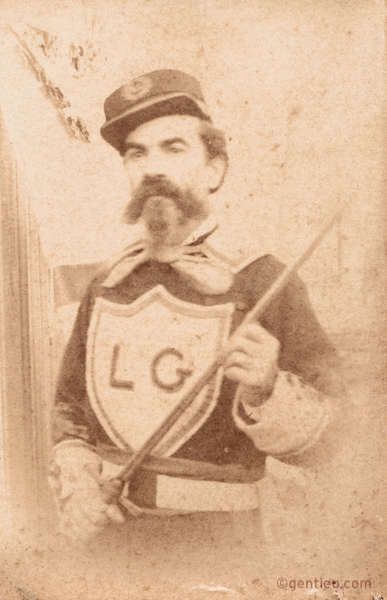

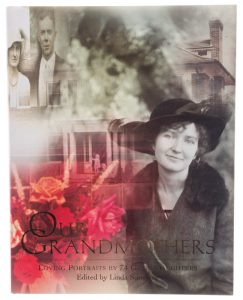

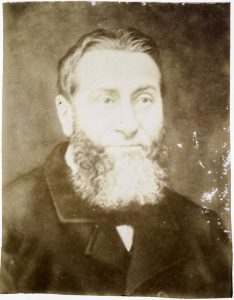

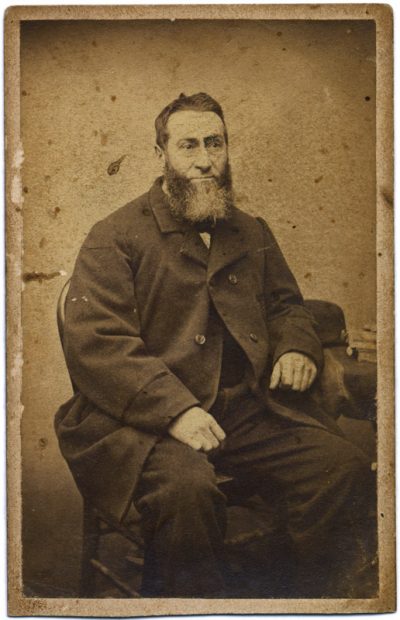

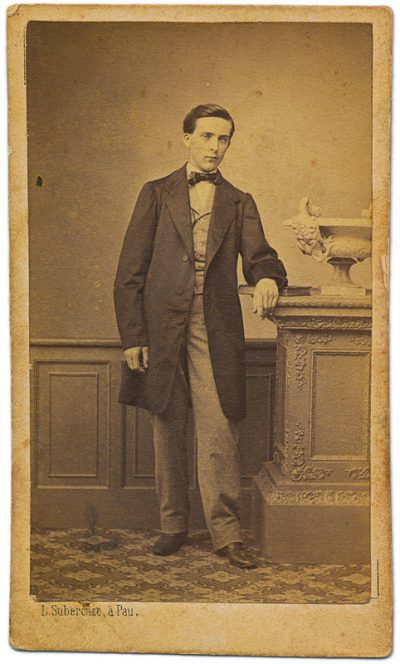

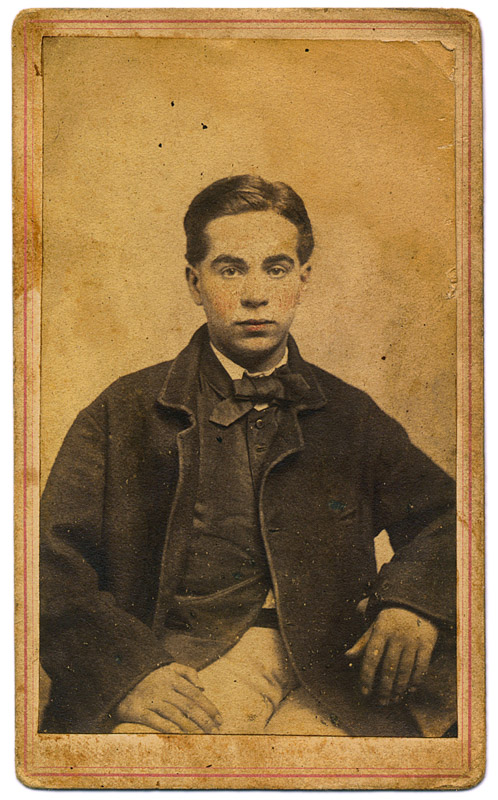

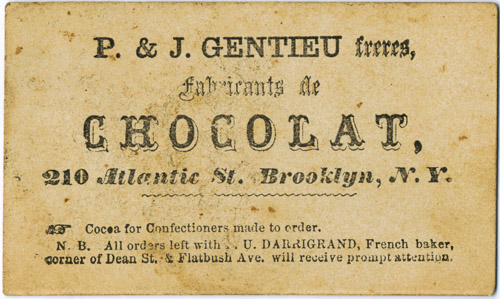

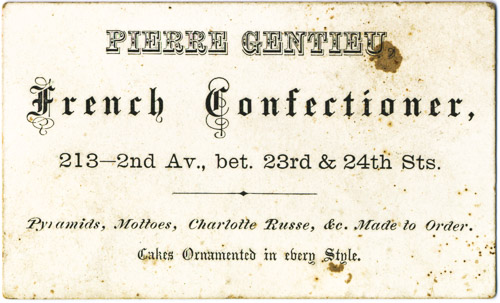

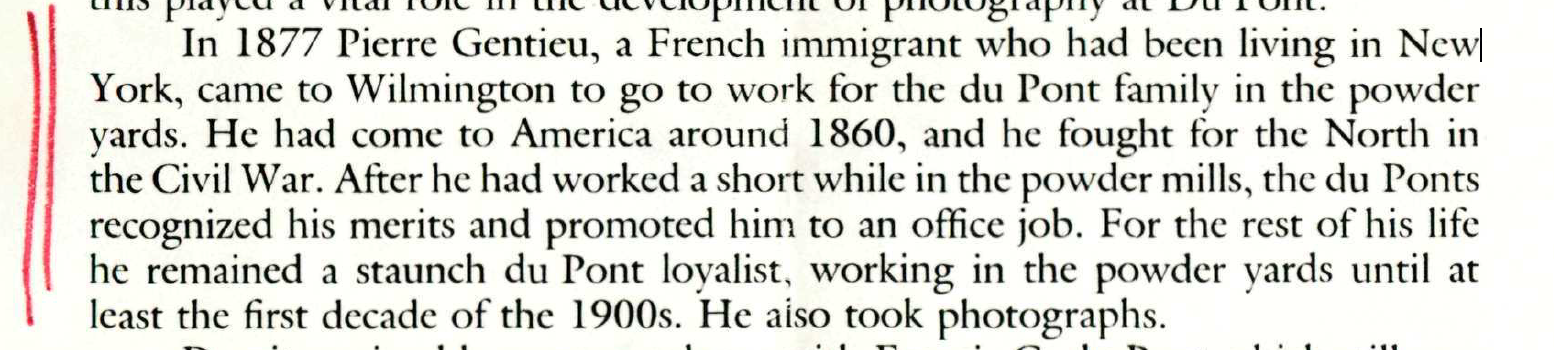

French photographer, Auguste Pondarre, and my great great grandfather, Pierre Gentieu, who emigrated from France in 1860, are two photographers whose work was not recognized until long after they died, but whose contributions to history, both worldly, and on a very personal level, are invaluable.

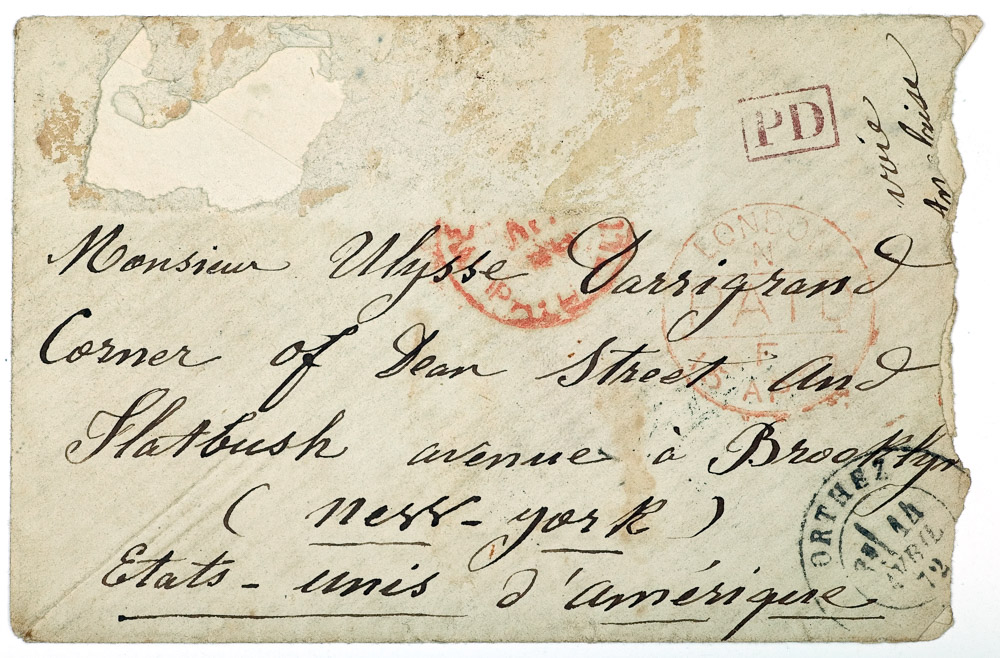

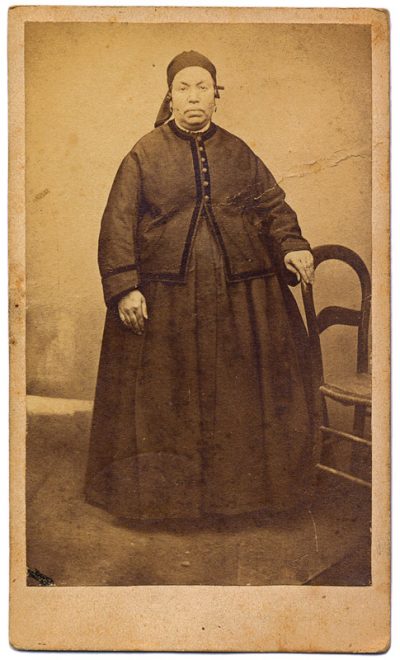

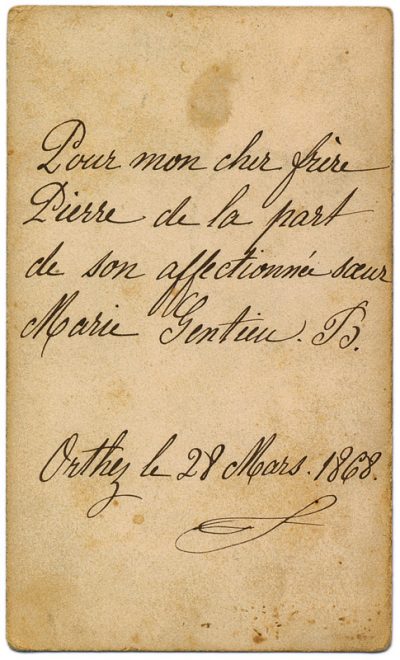

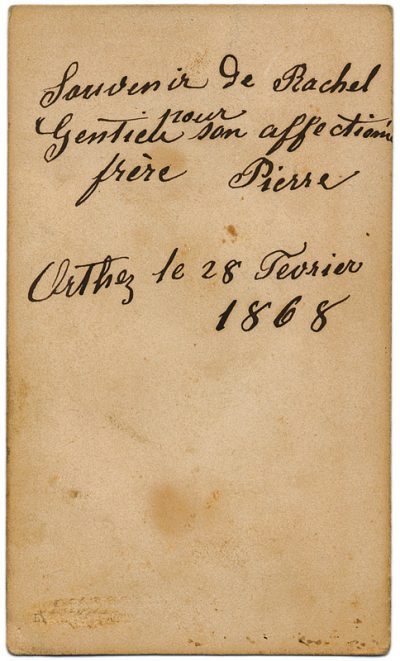

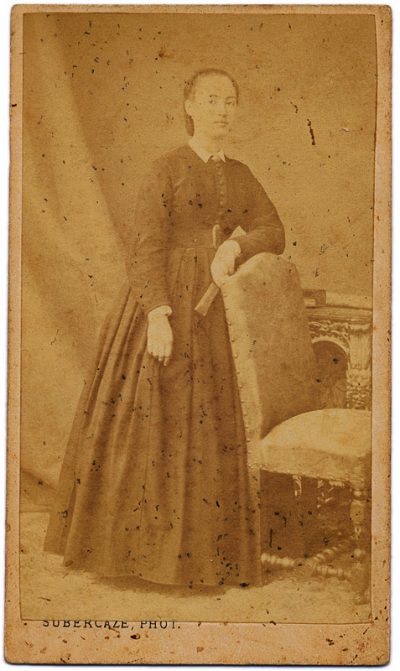

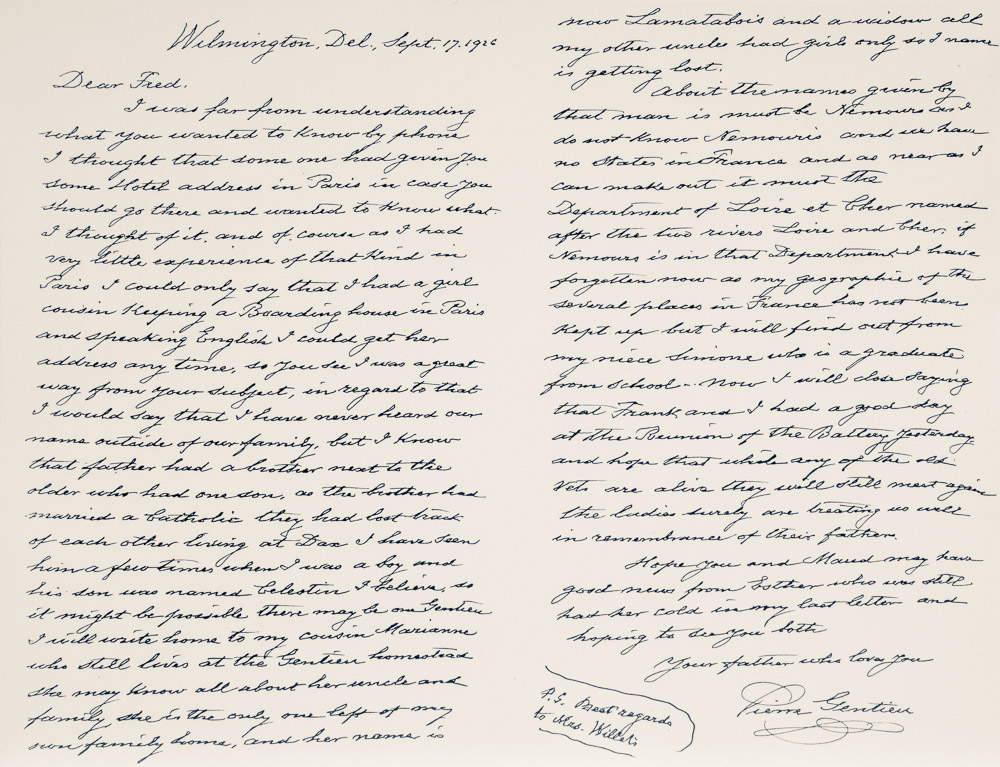

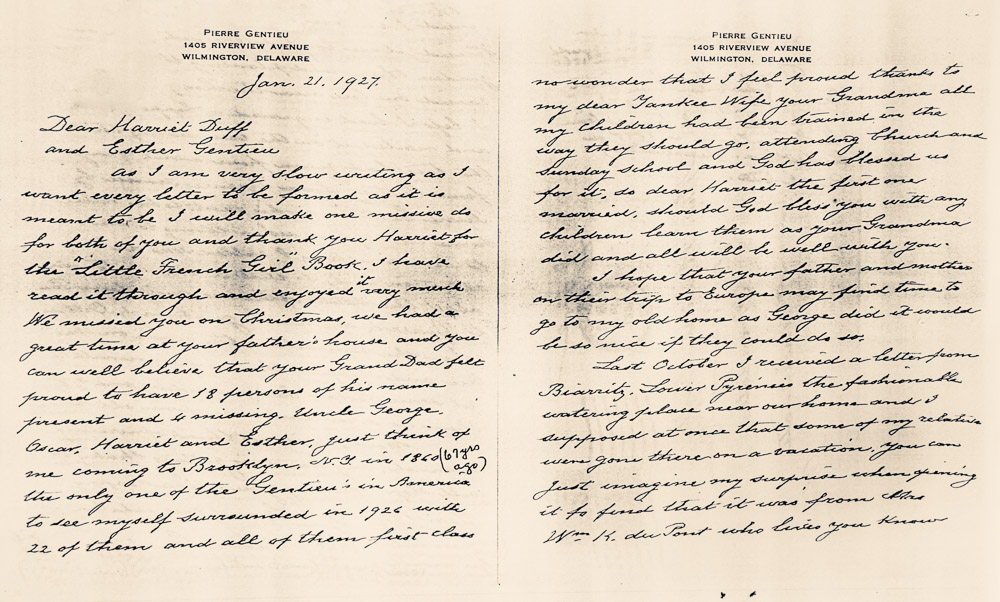

Auguste Pondarre (1871-1962) is Pierre’s nephew, the son of his sister, Marie. He lived in Orthez, Basses Pyrenees, France. He served in the French military from 1892 to 1895. He married Sarah Bessouat, a milliner, in 1905. They had a daughter, Simone, born in 1907. I met Simone in 1994.

After his service, Auguste worked with his father, Germain at his paint, art and frame shop on Rue de l’Horloge.

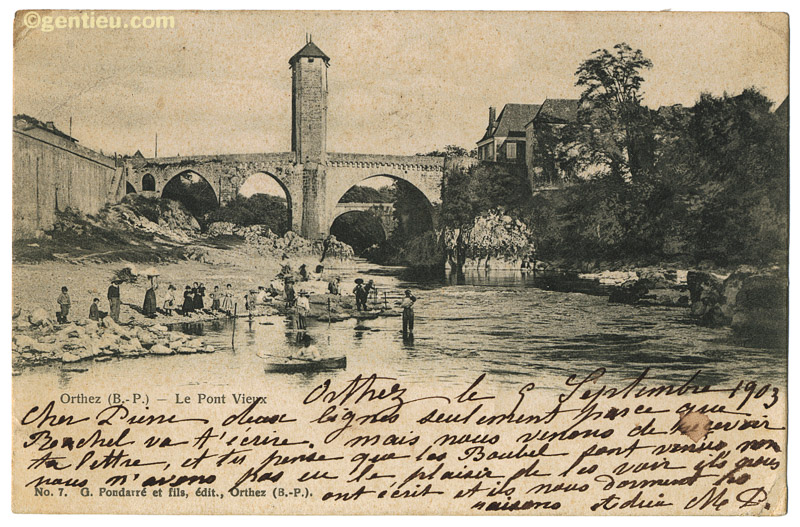

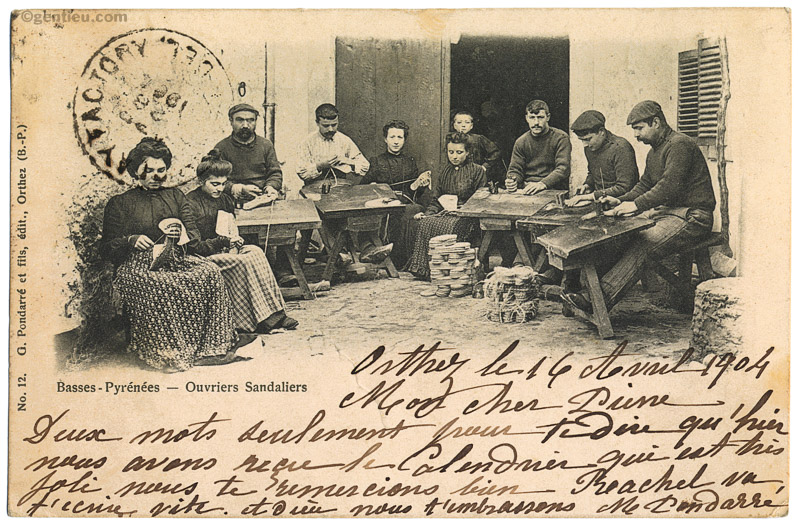

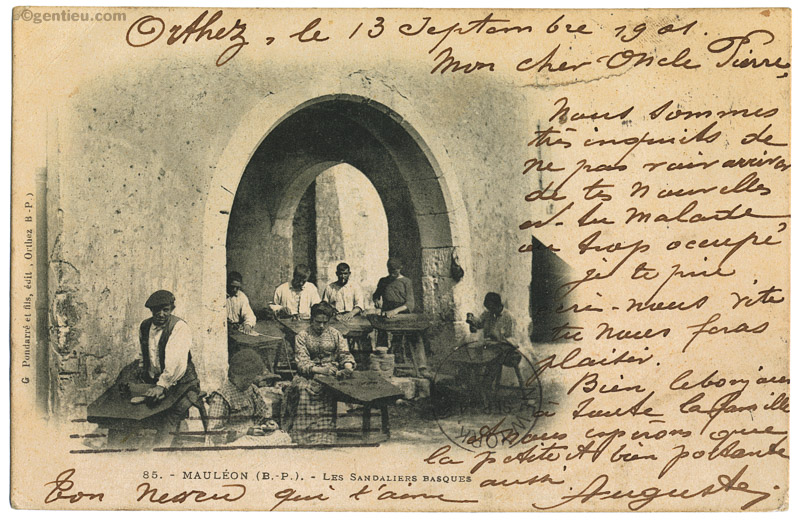

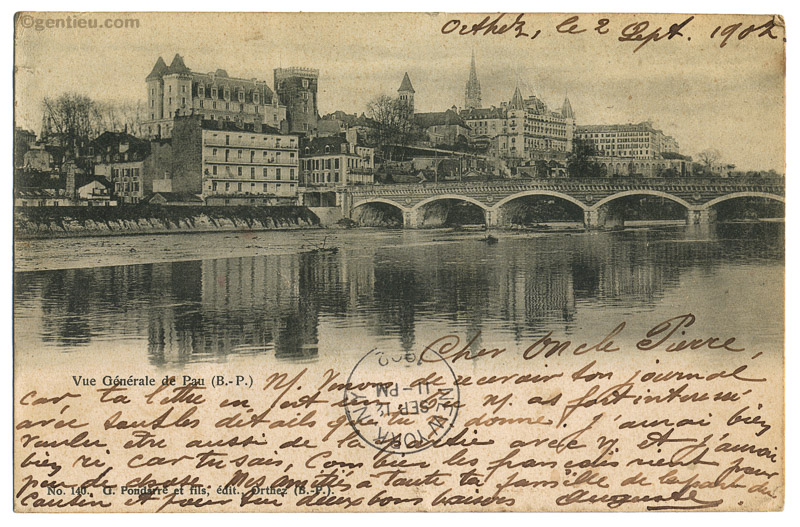

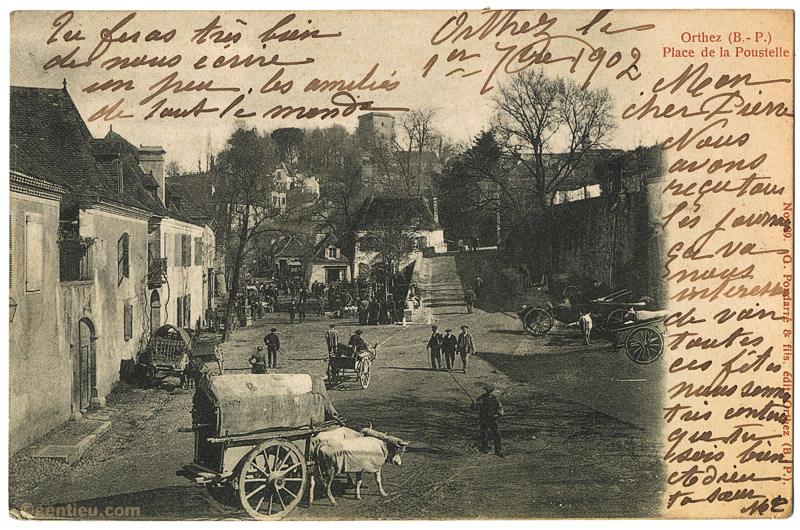

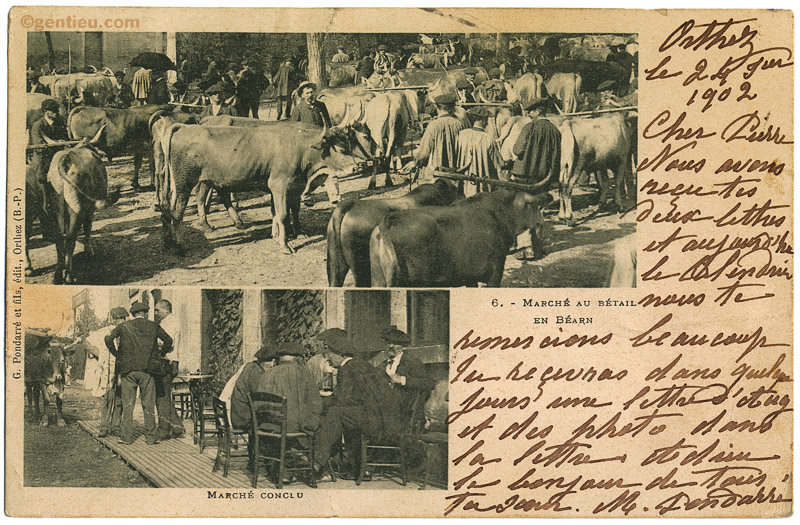

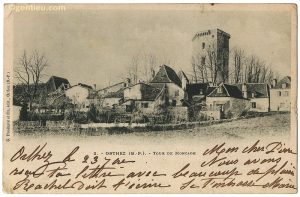

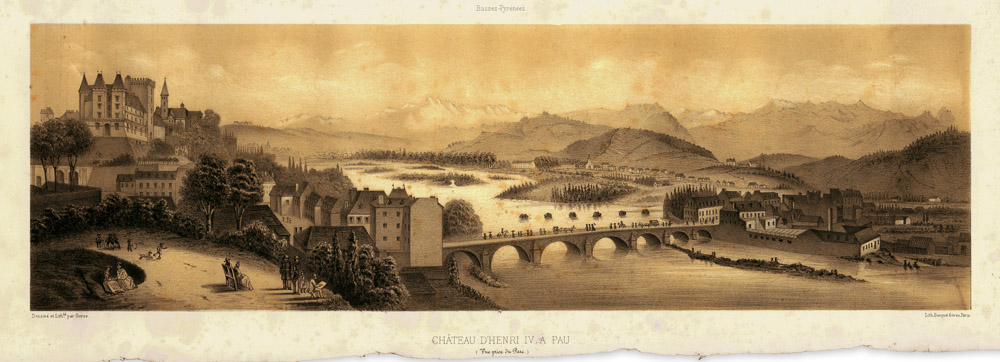

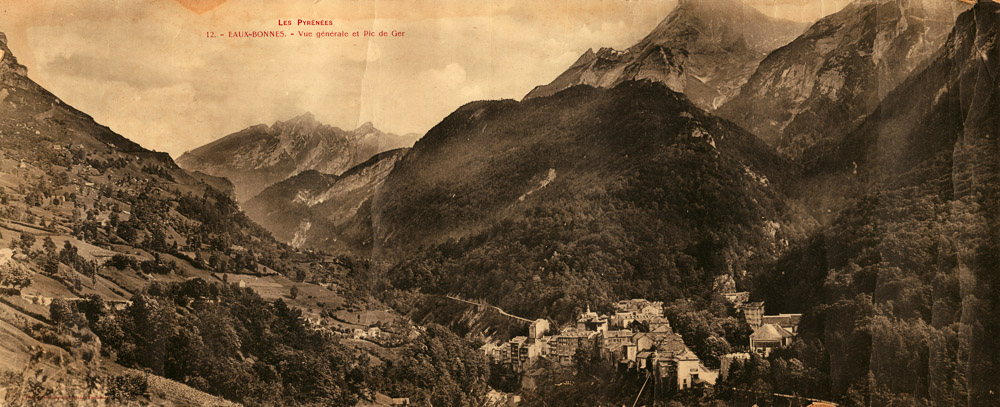

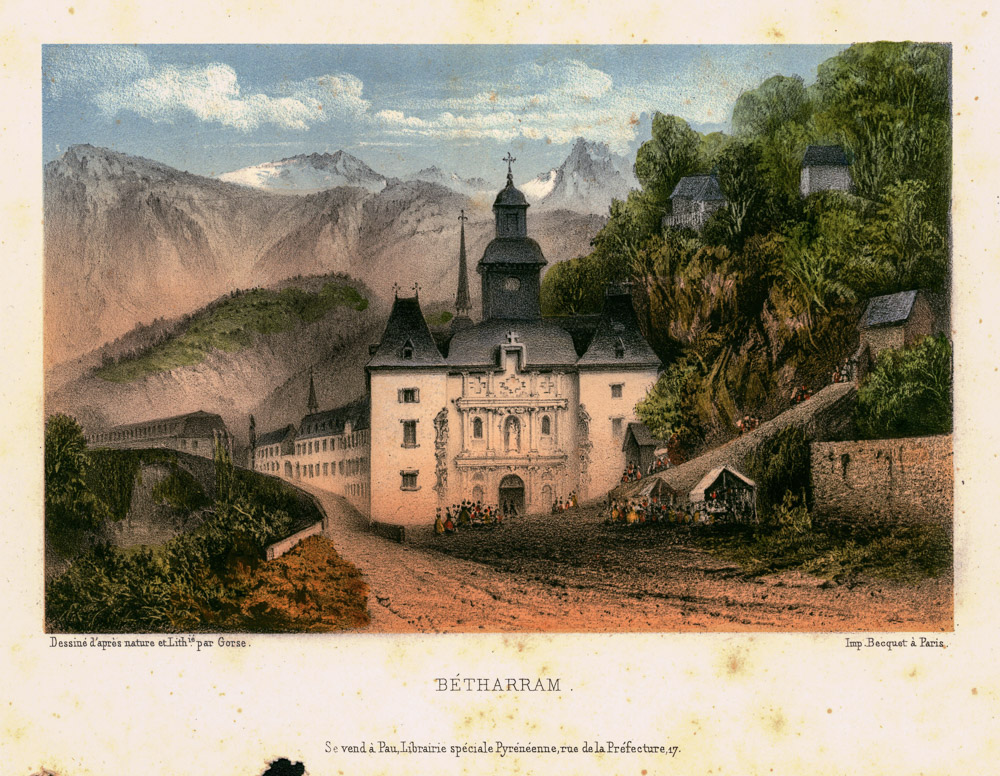

From 1901 to 1905, before he was married, Auguste made photographs of Orthez that were published as postcards under the name of his father’s shop, G. Pondarre & Fils.

Today, Auguste Pondarre is known for being the first photographer to create a photographic body of work that documents Orthez.

Could it be that his uncle, Pierre Gentieu, who had been creating photographs of the Brandywine Valley in America since 1880, inspired and influenced Auguste to make photographs? For that matter, who introduced Pierre to photography, was it someone in Orthez before he left for America?

I have some clues.

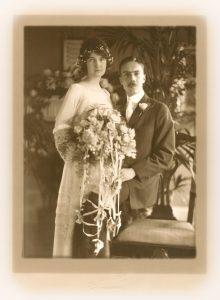

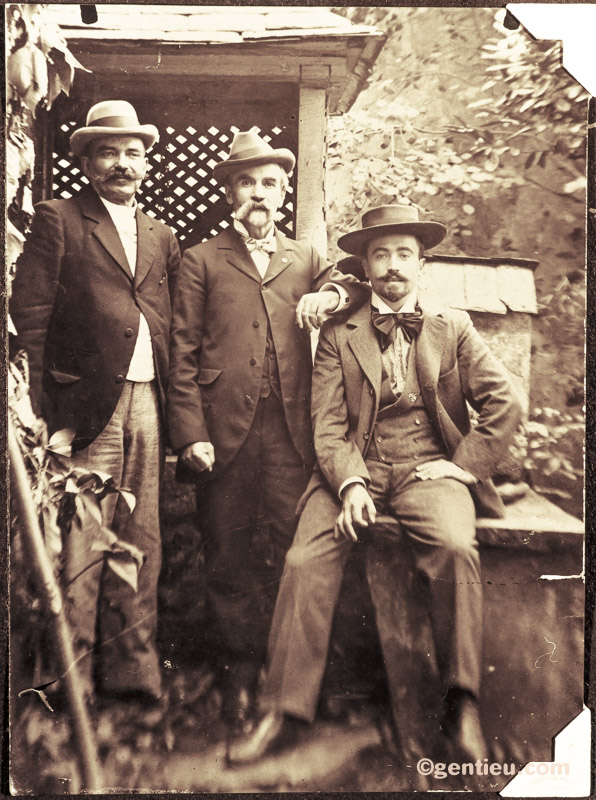

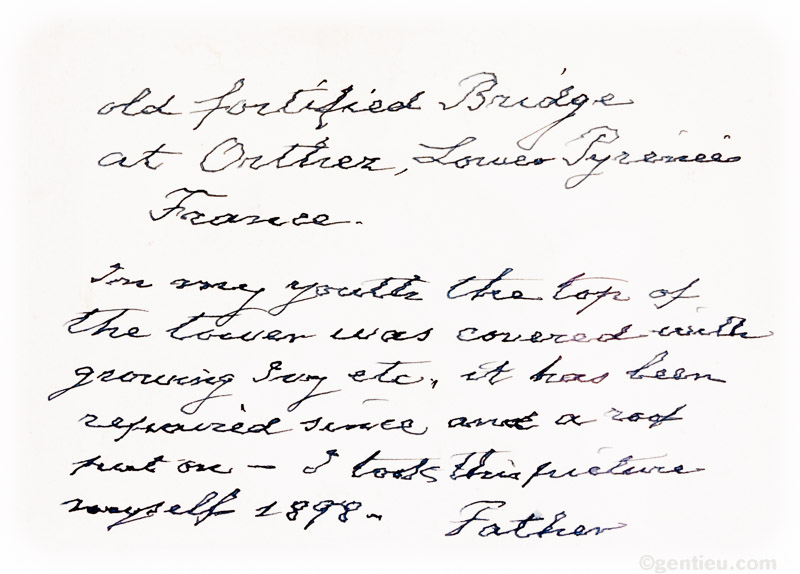

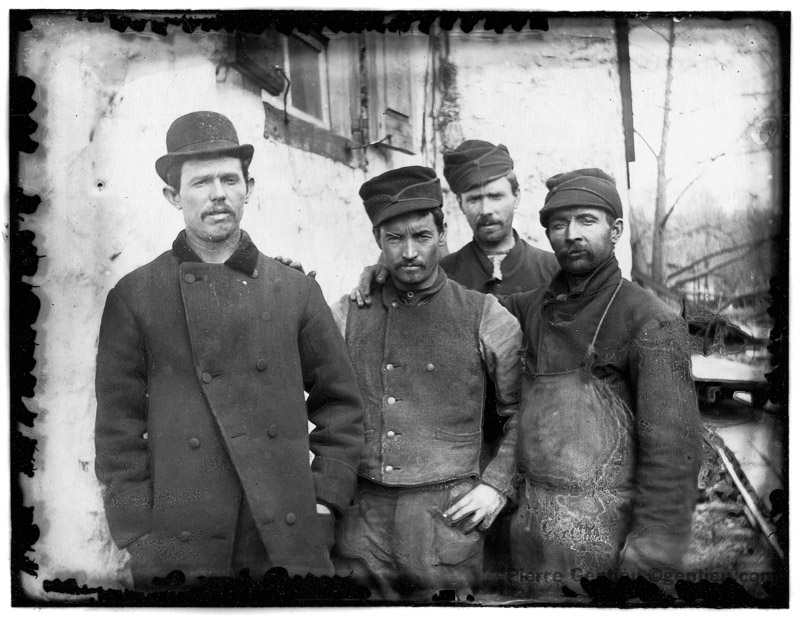

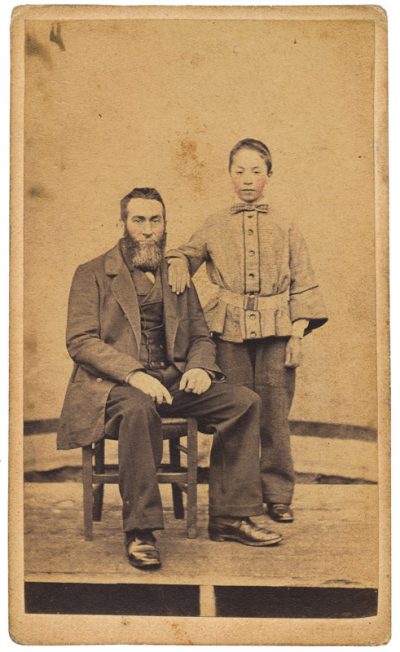

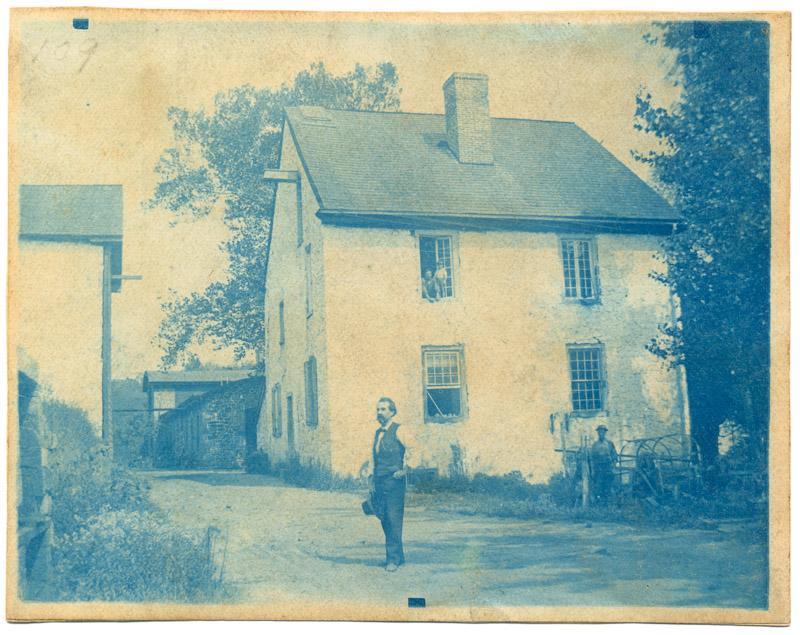

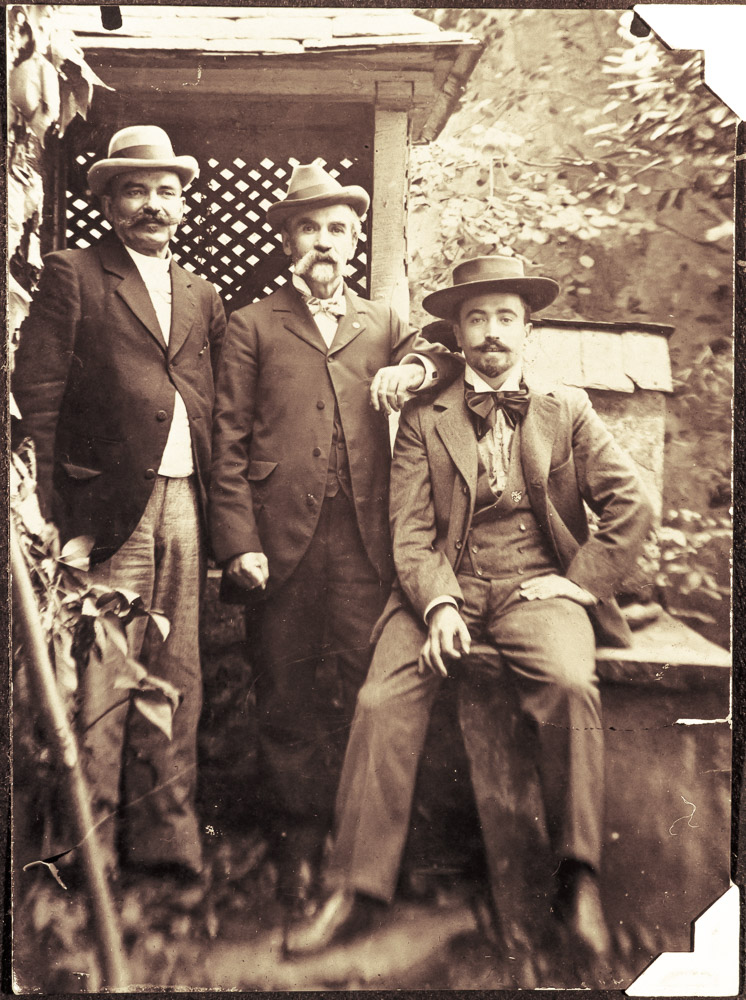

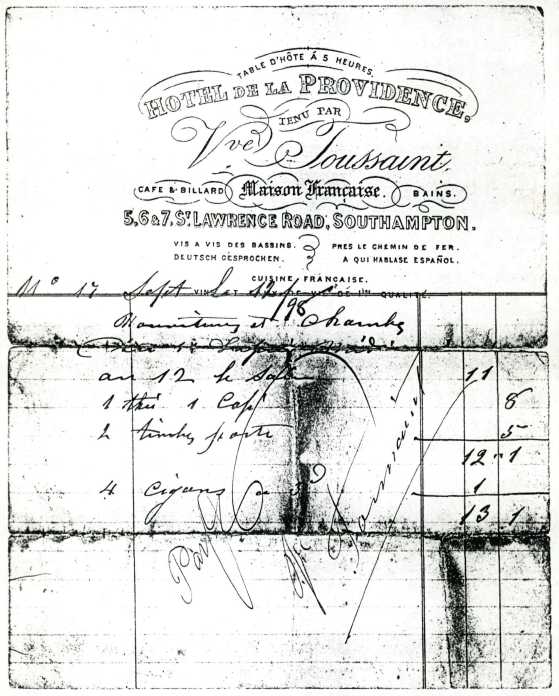

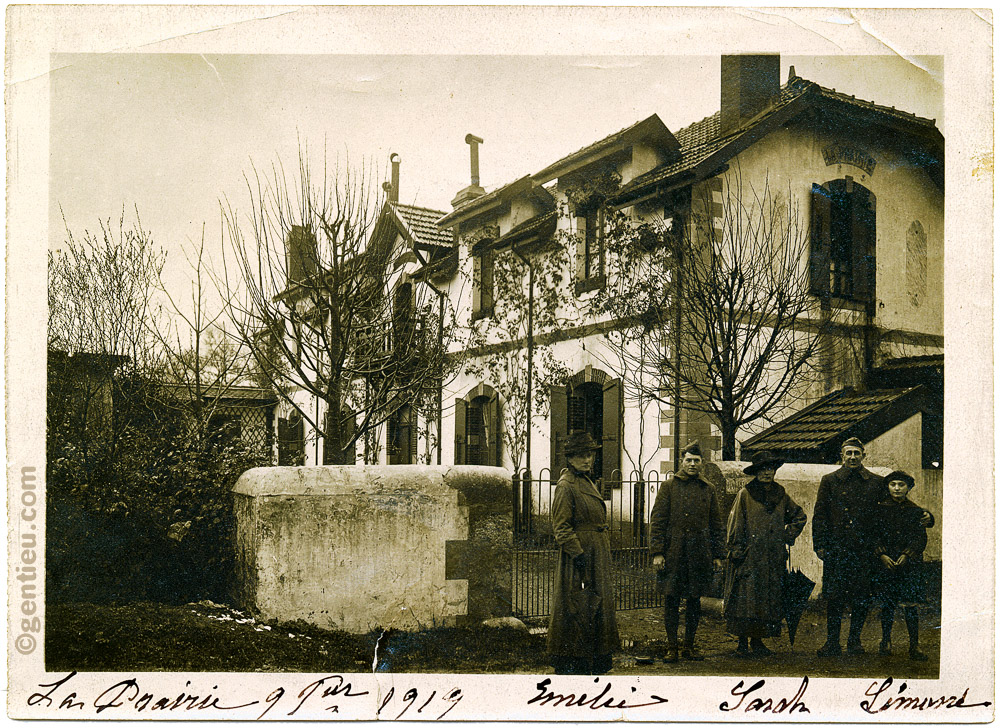

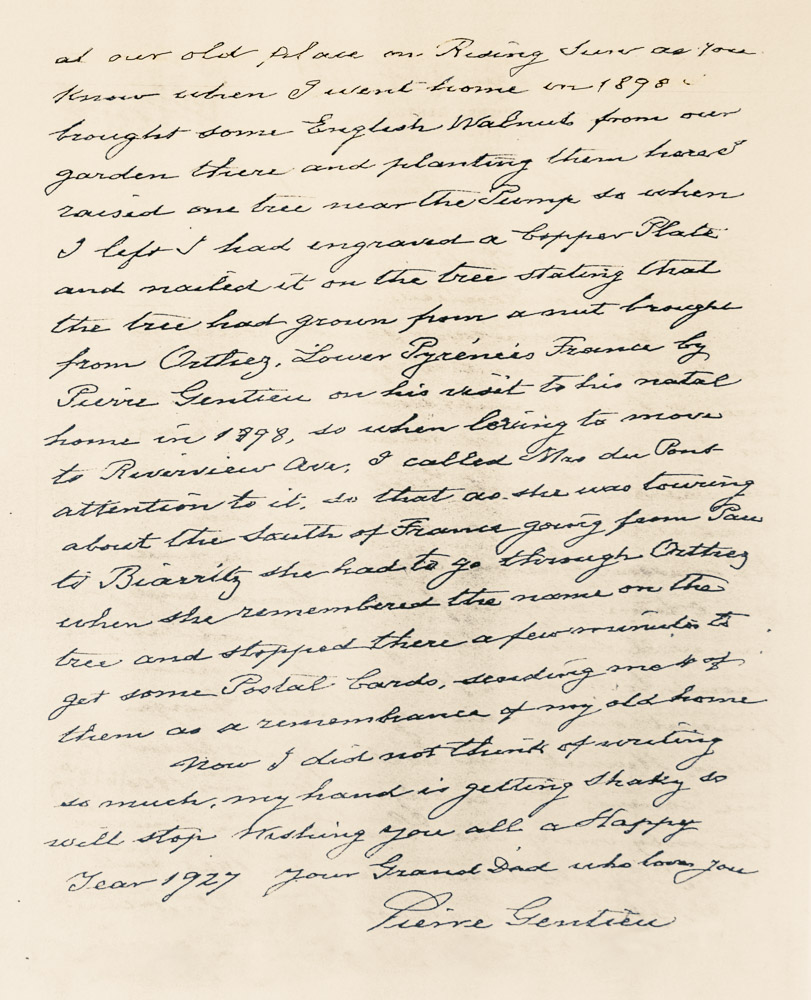

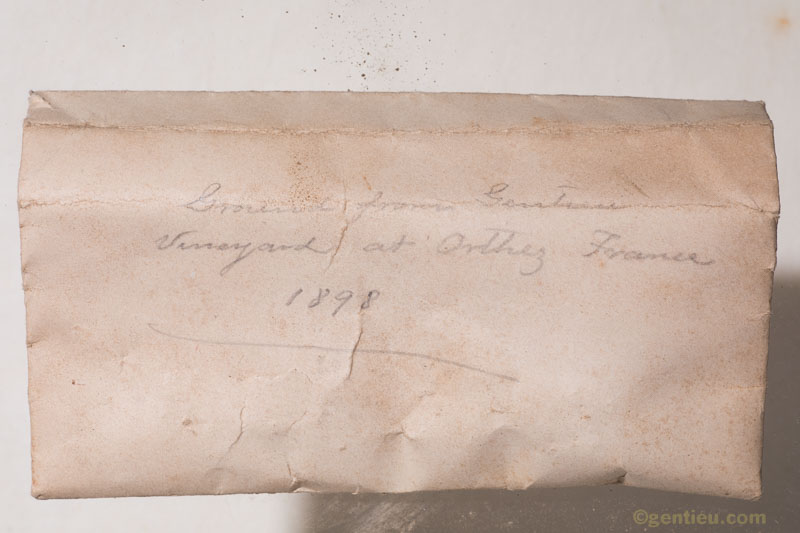

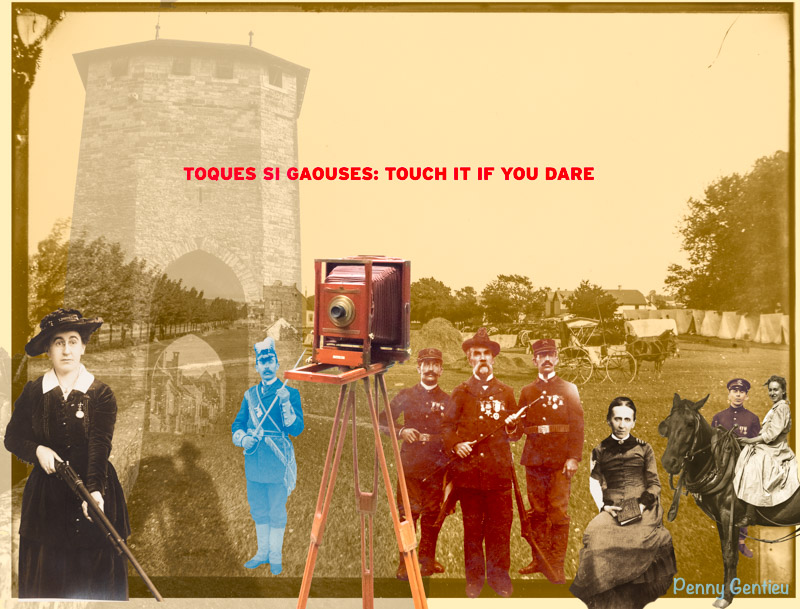

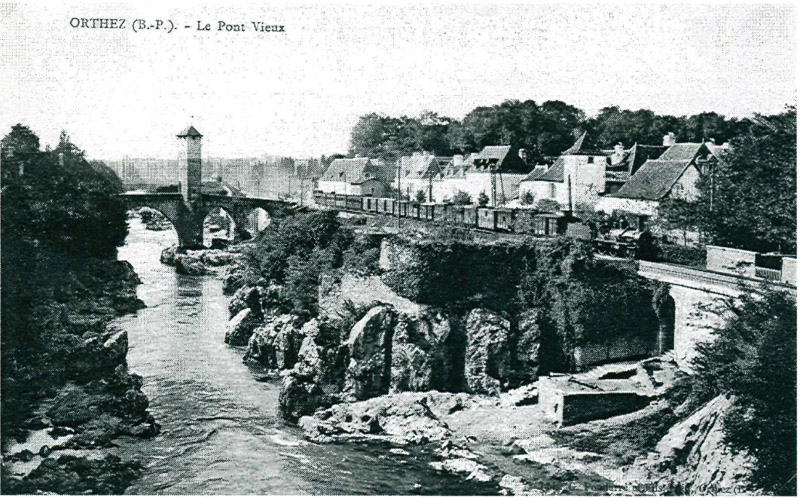

Pierre visited Orthez in August and September, 1898. He took his camera with him and made, at least, these three photos, that have survived.

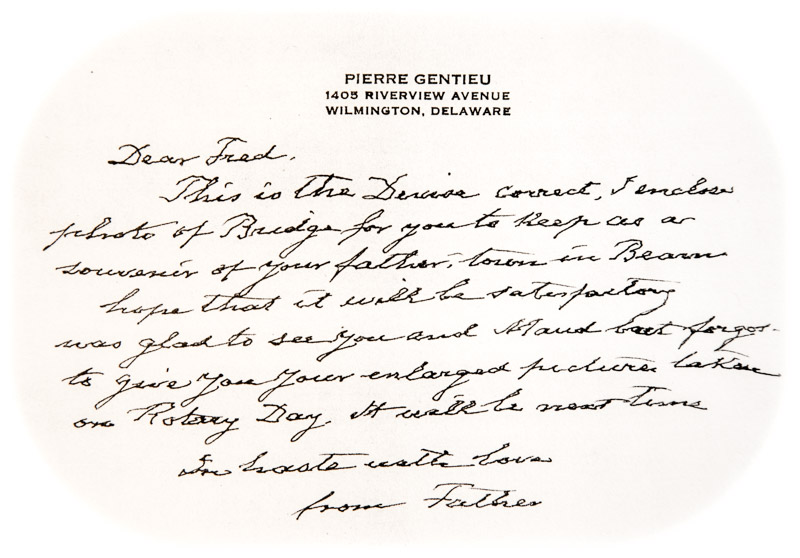

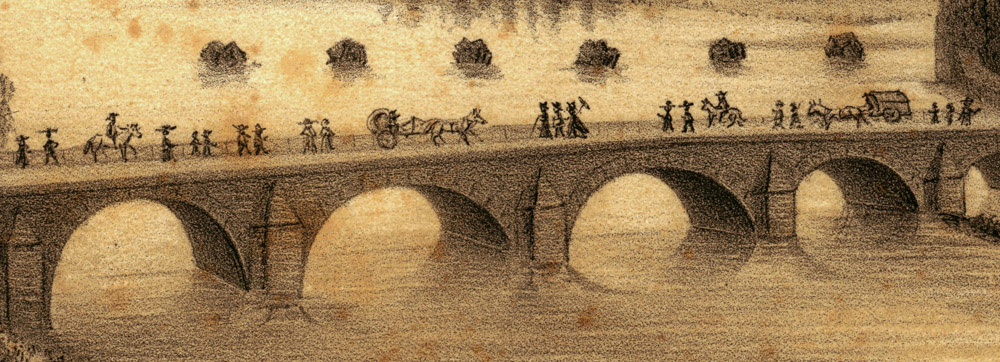

Germain Pondarre, Pierre Gentieu, Auguste Pondarre; Gentieu-Baillan chocolate shop with sisters Marie Pondarre and Rachel Gentieu; the ancient Orthez bridge, which Pierre printed again in the late 1920's, writing a note on the back about the restored tower and that he took the photo in 1898.

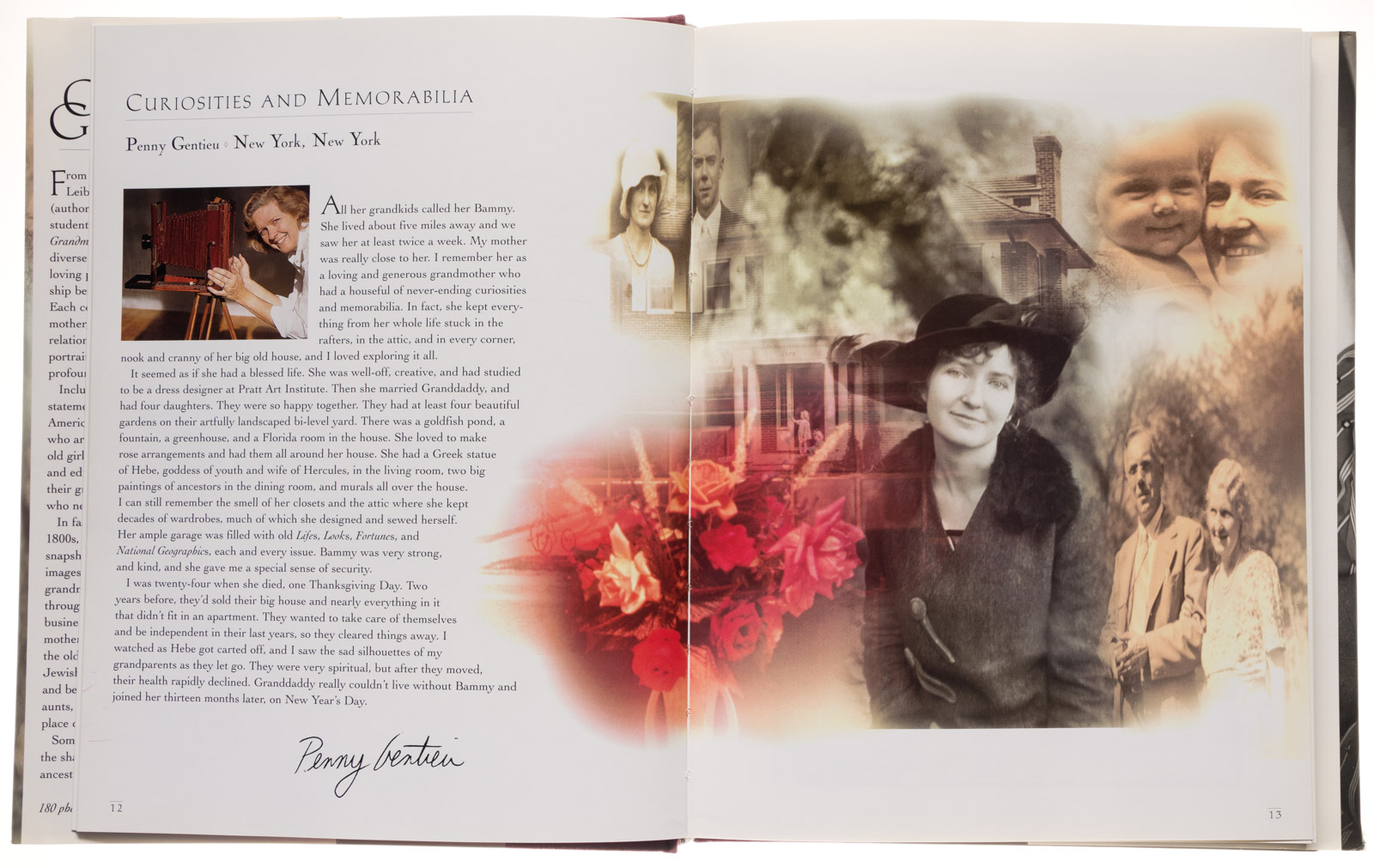

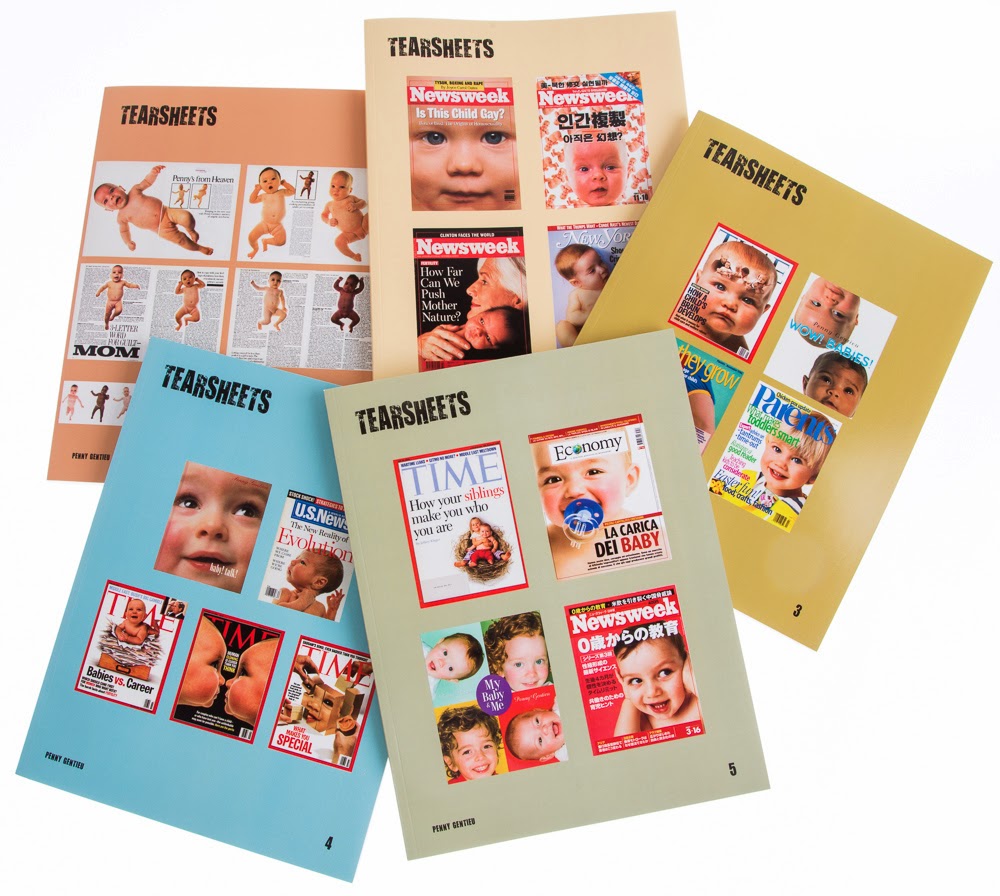

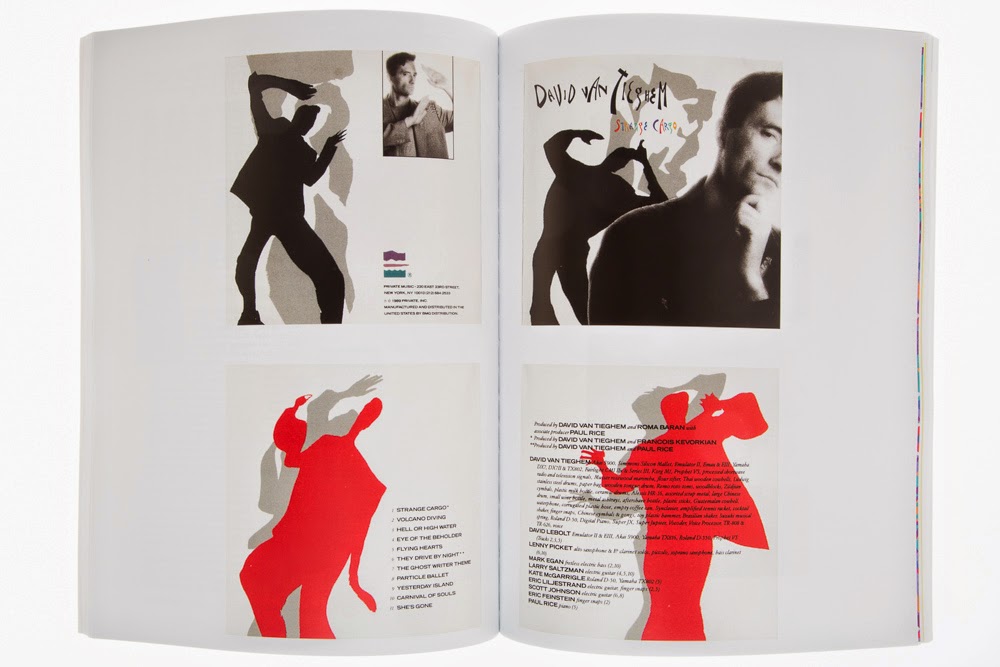

The book, Duex Photographs Ortheziens du Debut di Siecle

I found a book that Simone sent to me in 1998, Duex Photographs Ortheziens du Debut di Siecle (Two Orthezien Photographers at the Start of the Century) by Jean Teitgen, about the first two photographers of Orthez that left a body of work, Auguste being the first, and their postcards.

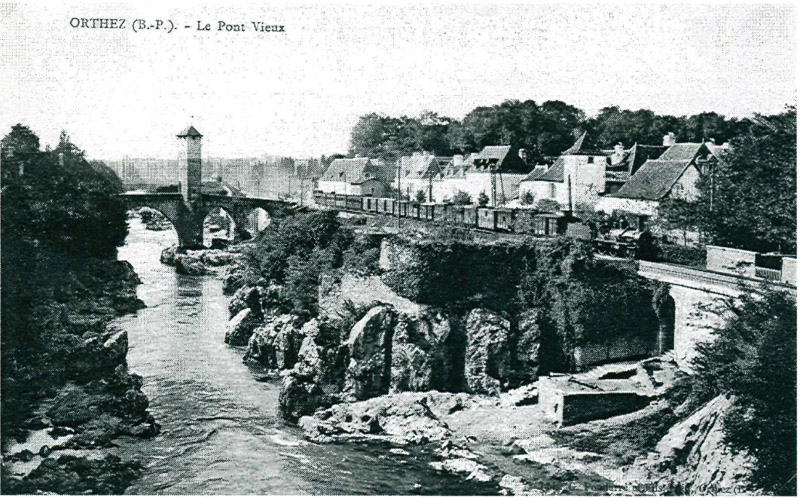

In the book is this photo of the bridge by Auguste Pondarre:

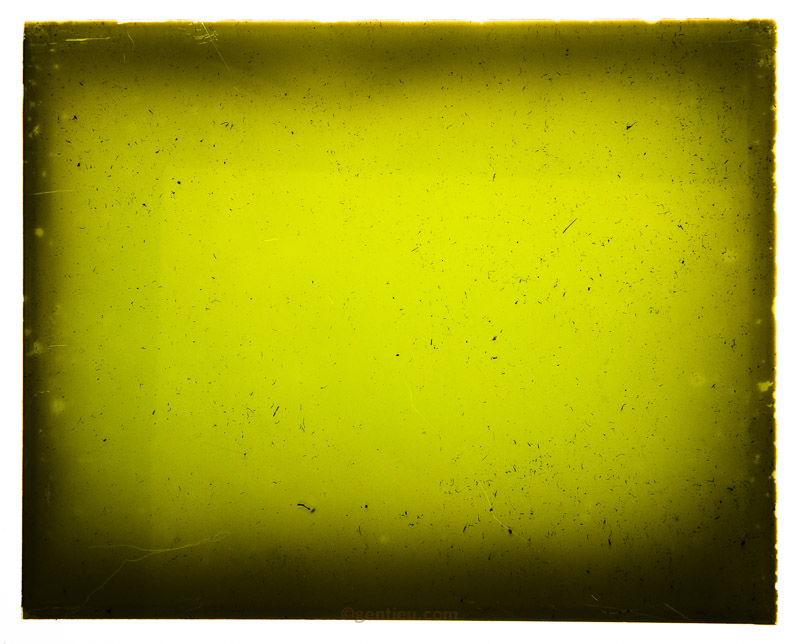

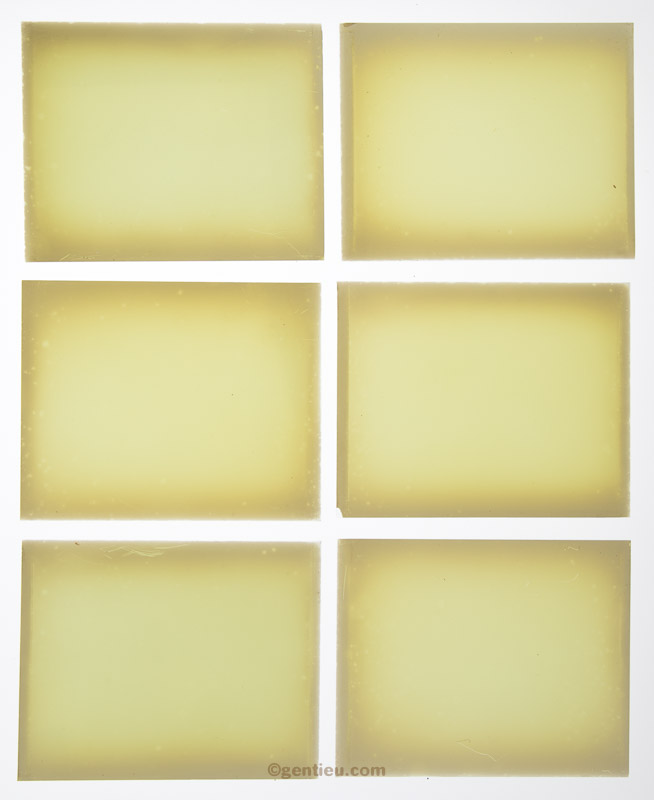

Auguste’s photo of the bridge is nearly identical to Pierre’s photo, taken from the same spot, close to the same time, but perhaps years apart, because of the evidence of grown ivy on the rocks to the right. The lens was the same focal length and it was captured on the same size quarter plate, 4×5 glass negative.

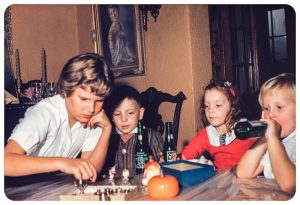

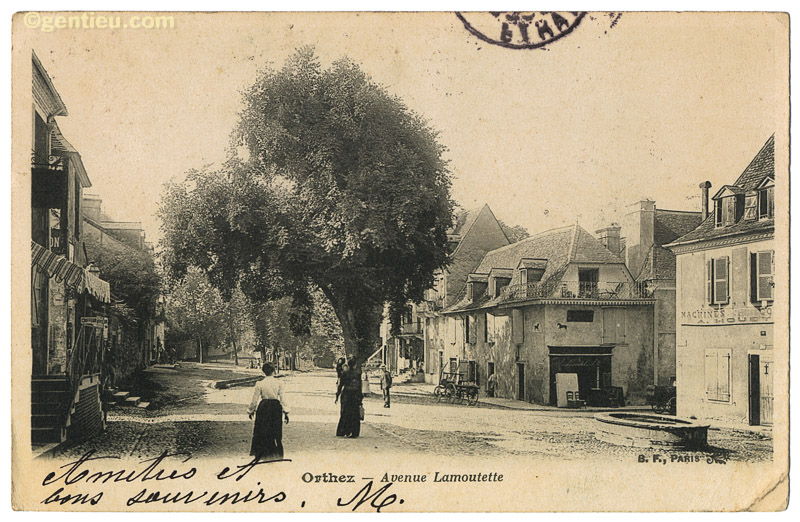

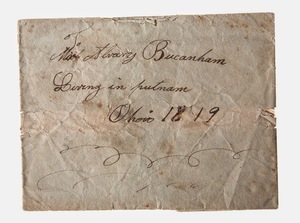

Some Pondarre postcards received by Pierre, dated 1901 to 1905

Auguste Pondarre's important early photos of Orthez first received recognition in the 1980's with an exhibition of his postcards.

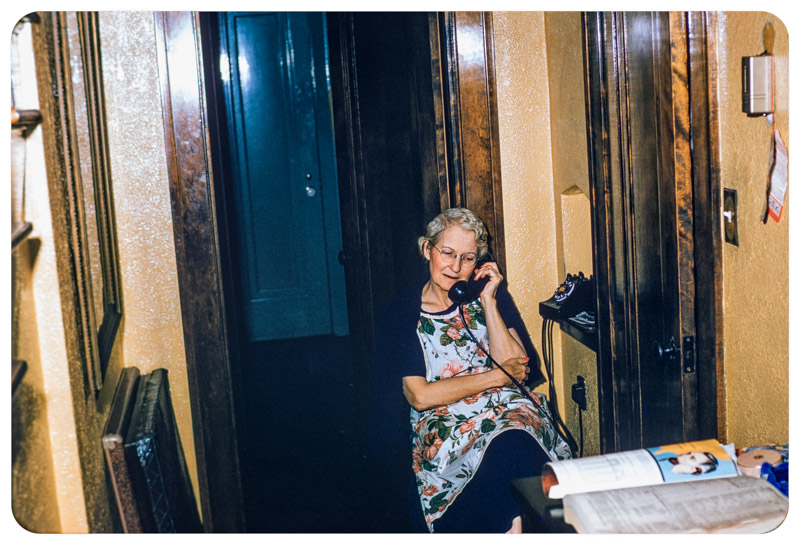

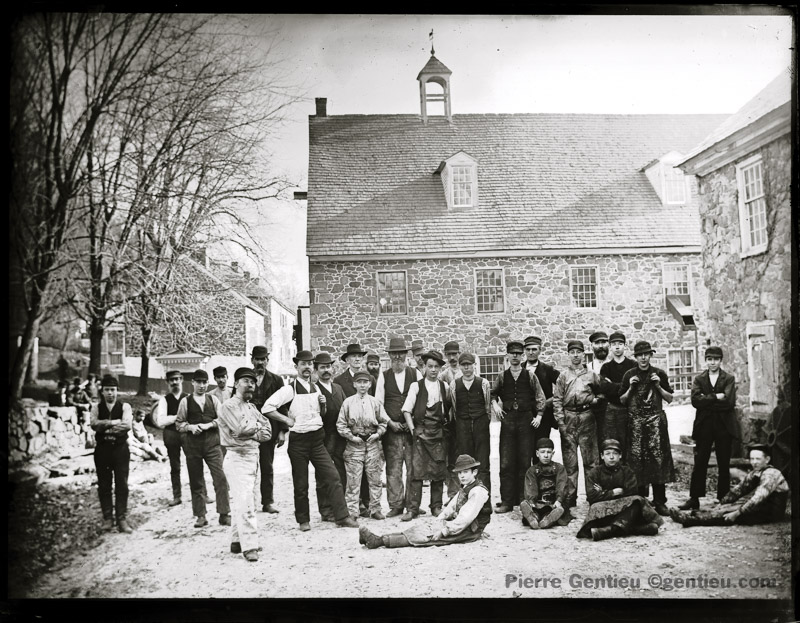

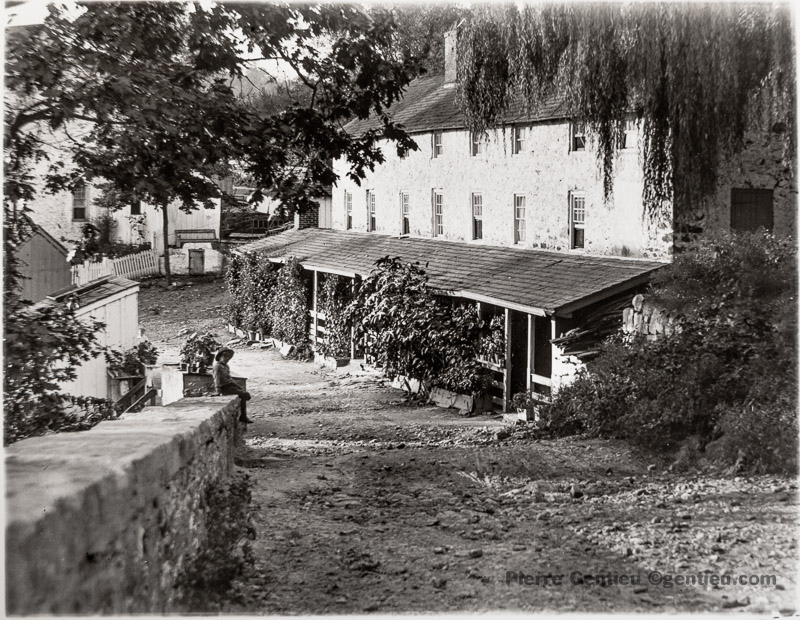

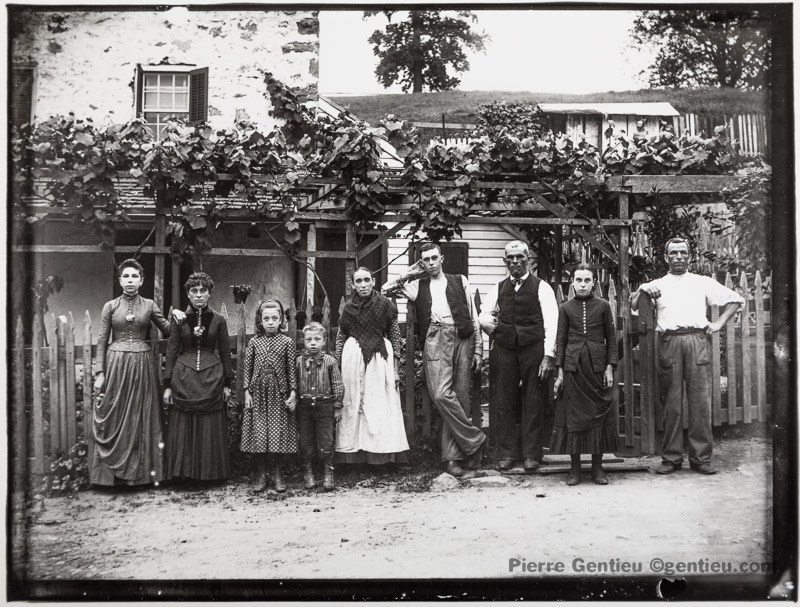

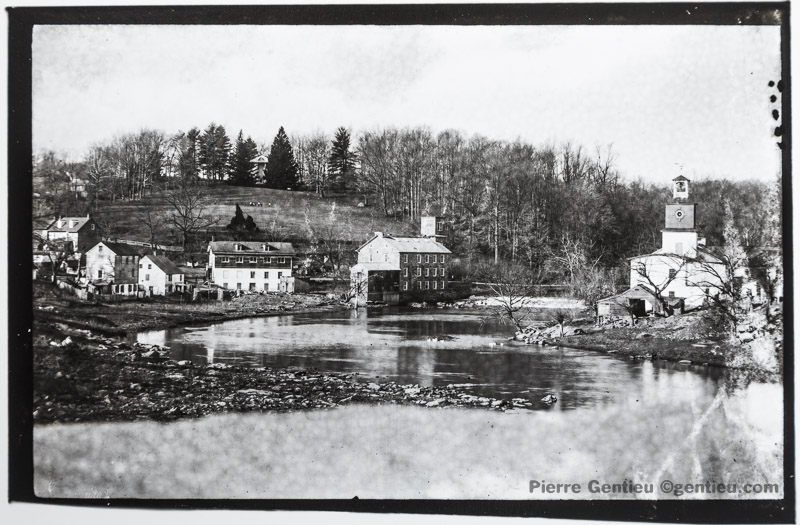

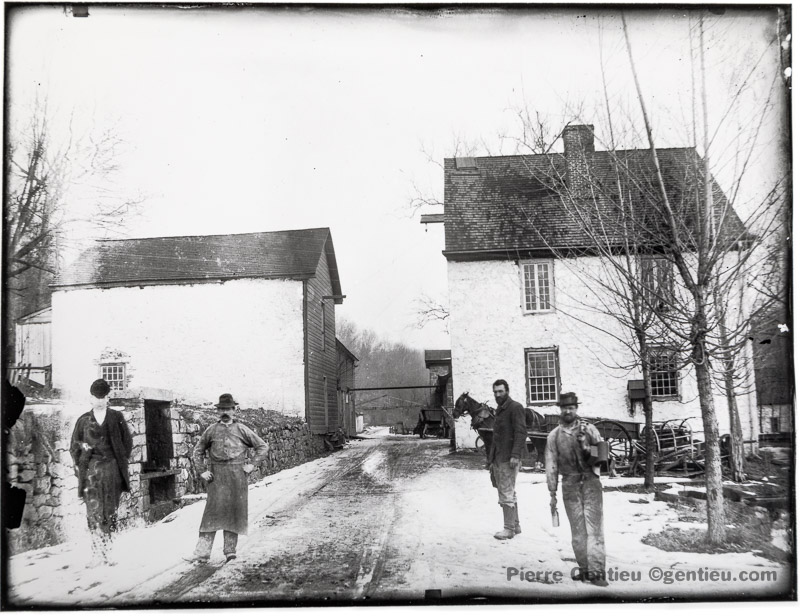

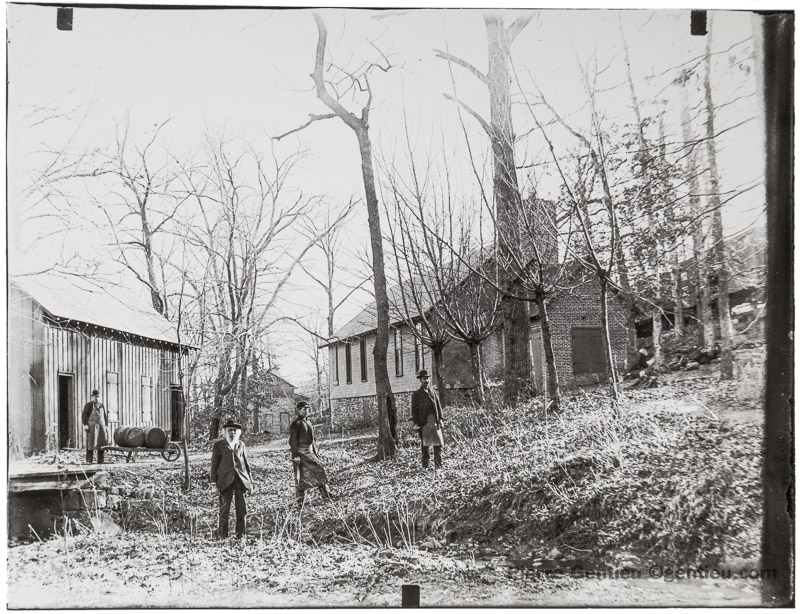

Some Gentieu photographs of the Brandywine Valley, a body of work that Pierre began in 1880 and worked on for nearly 40 years:

Pierre Gentieu's documentary photographs of the DuPont Powder Company and the lifestyle of the workers of the Brandywine Valley received recognition in the 1970's, when his collection became invaluable for the creation of the Hagley living history museum in Delaware.

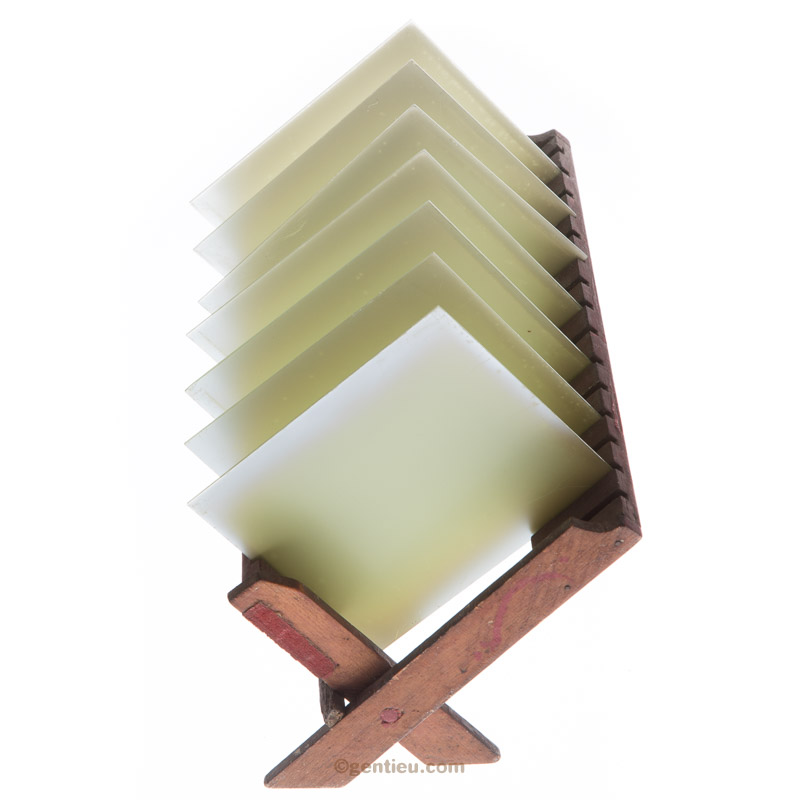

Their cameras

Pierre’s camera is on the left. Auguste’s camera is on the right, which I photographed at Simone’s house. Pierre’s camera can expose a glass negative as large as 8×10. Auguste’s camera appears to be 6.5×8.5, but both cameras accommodate half and quarter glass plate negative sizes.

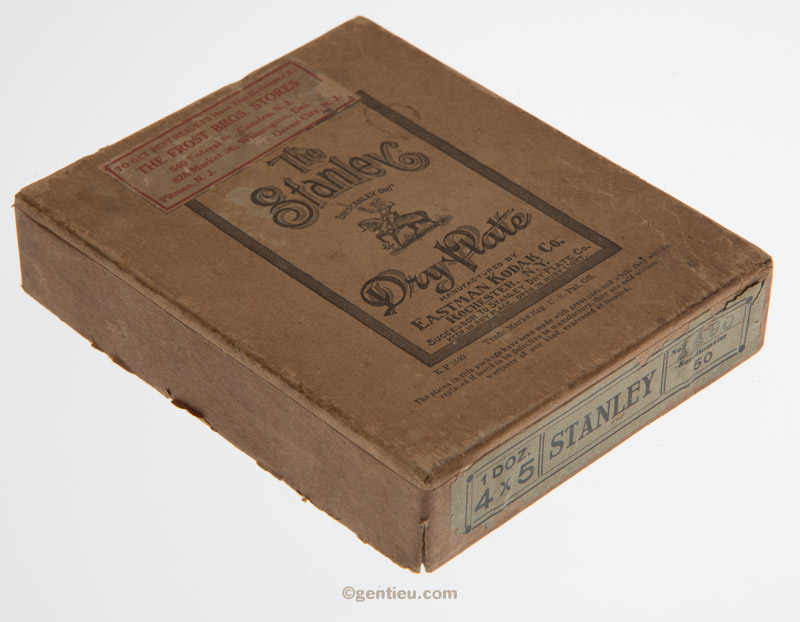

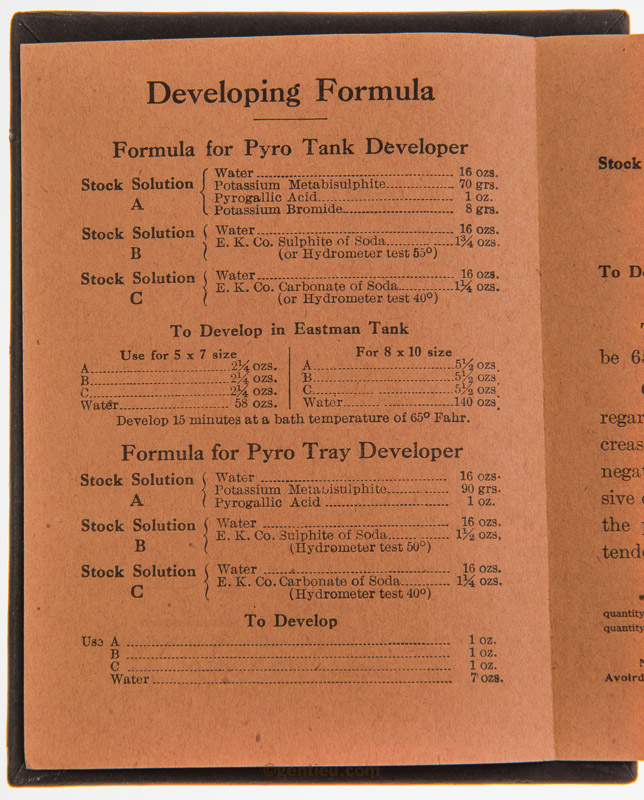

The equipment Pierre used and would bring with him to Orthez in the summer of 1898:

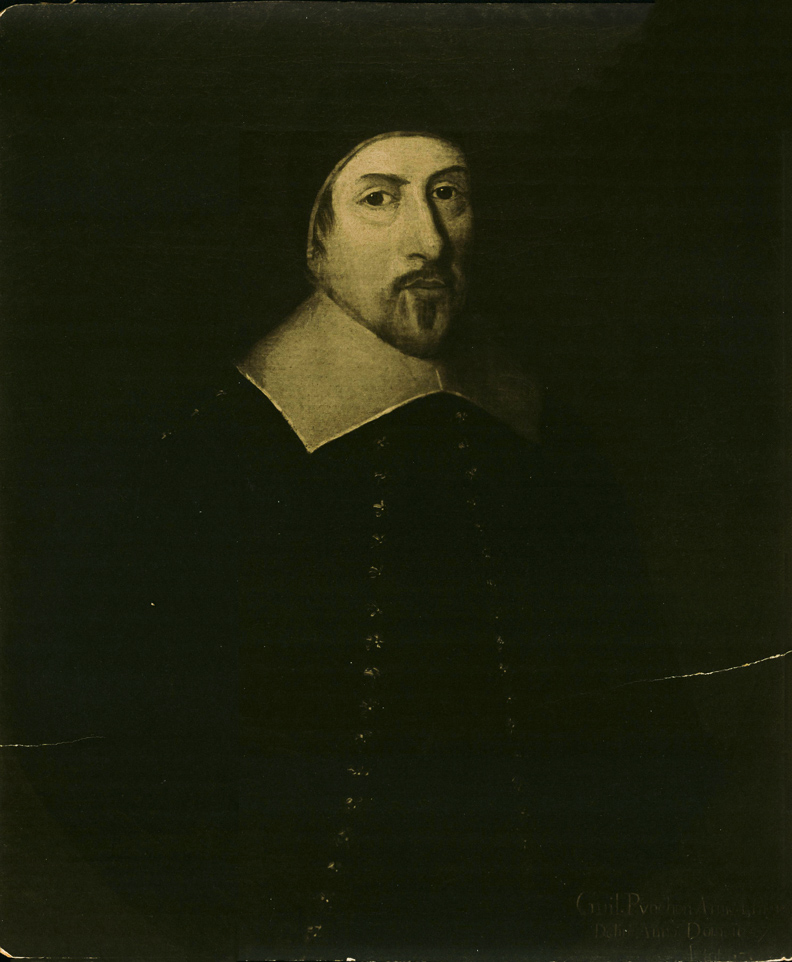

According to the biographical details in the French book about Auguste’s life, Germain and Marie were living in Bayonne, where Auguste was born. Toward the end of the nineteeth century, the family moved to Orthez to live at the old Gentieu homestead with Marie’s sister, Rachel. Perhaps it was around 1891, when the mother, Anne Celeste Gentieu-Baillan died, who had been living there with Rachel. The Pondarres remained at the old Gentieu home until 1911, when they bought a building and moved up the street. Auguste served in the military from 1892 to 1895, returning to Orthez at age 24, and going to work as a house painter in his father’s business.

Pierre visited Orthez in 1898, presumably staying with his two sisters, Marie and Rachel, along with Germain and Auguste. Pierre brought along his camera and processing equipment. Could it be that Pierre’s photography interested Auguste? Perhaps Auguste was with him when he photographed the bridge and other scenes.

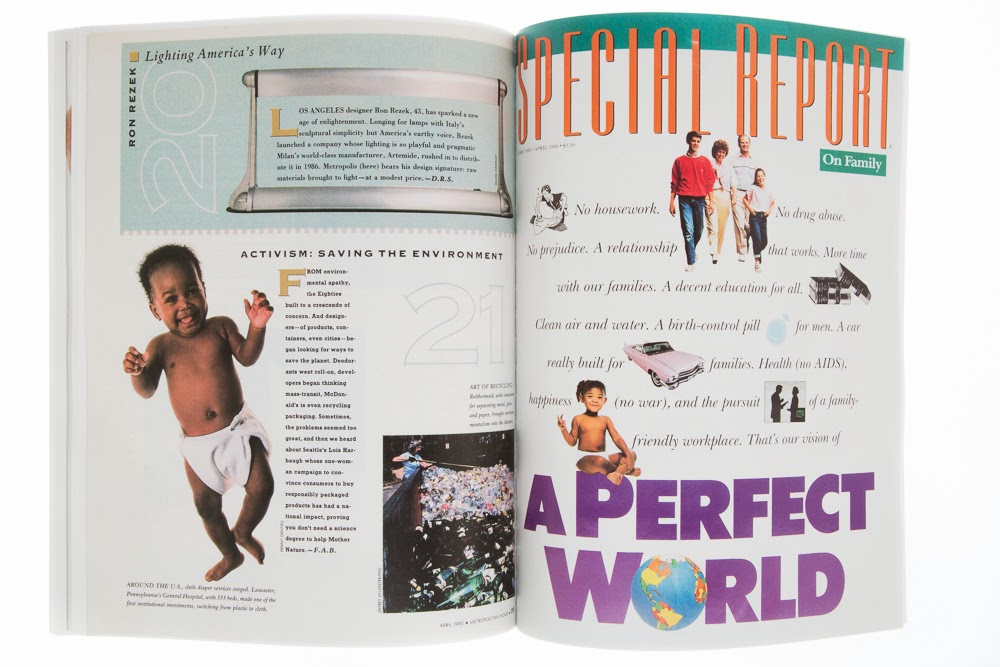

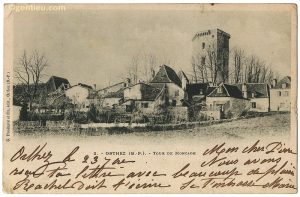

This postcard shows the backyard of 54 rue Moncade, the address of the ancient Gentieu homestead, and surrounding houses, with the castle ruins Tour Moncade across the street from these buildings. It is Auguste’s card number 2, printed in 1901.

If Pierre influenced Auguste, who influenced Pierre?

It is ironic that a hint comes from a detail about the second photographer subject of the book, Duex Photographs Ortheziens du Debut di Siecle. Joseph Barbe was five years younger than Auguste. At age 20, he opened a portrait studio in Orthez in 1896. In 1903, perhaps at the suggestion of Auguste, Joseph Barbe moved his studio next to the Pondarre art shop on Rue de l’Horloge, and started producing images for postcards, as a complement to his portrait business. Auguste stopped publishing postcards in 1905. The author of the French book asks the question, where did Joseph Barbe get his inspiration to be a photographer? The suggestion is that it was through Andre Laffitte-Forsans, one of the first persons to own a camera in Orthez.

Laffitte was Pierre Gentieu’s great grandmother’s maiden name

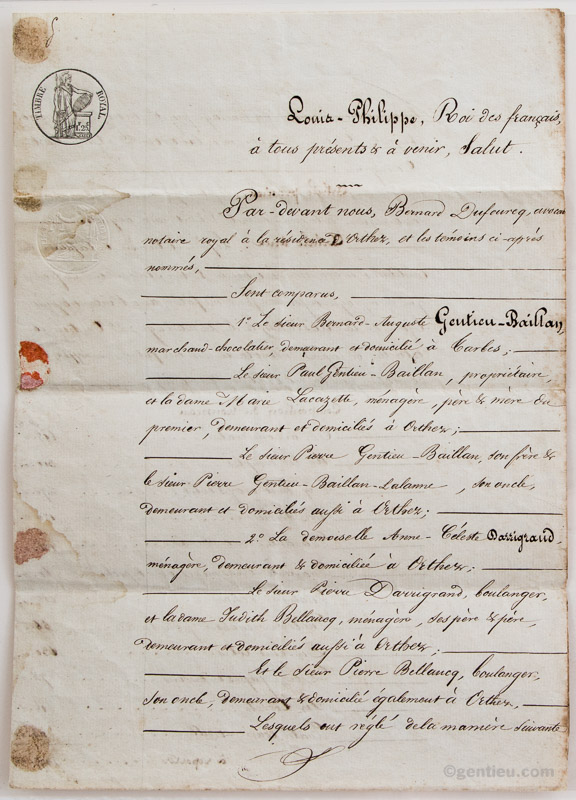

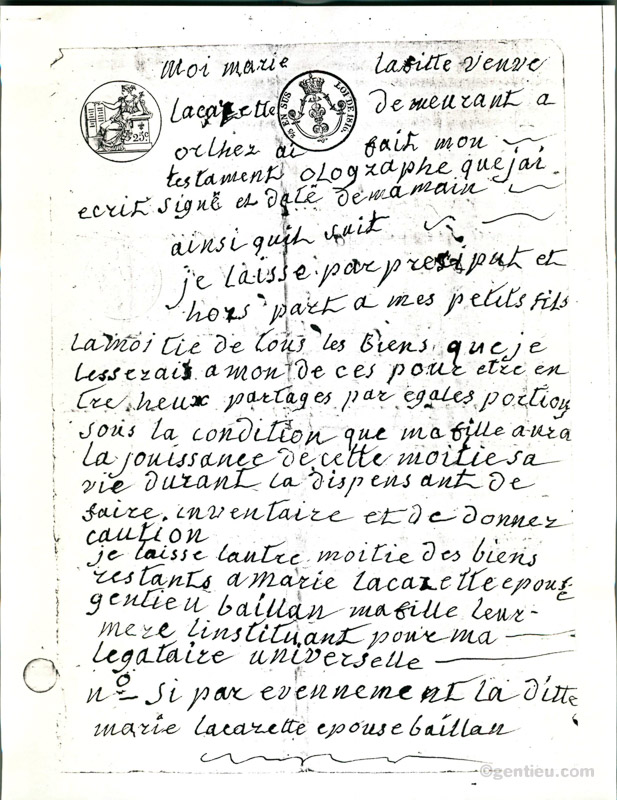

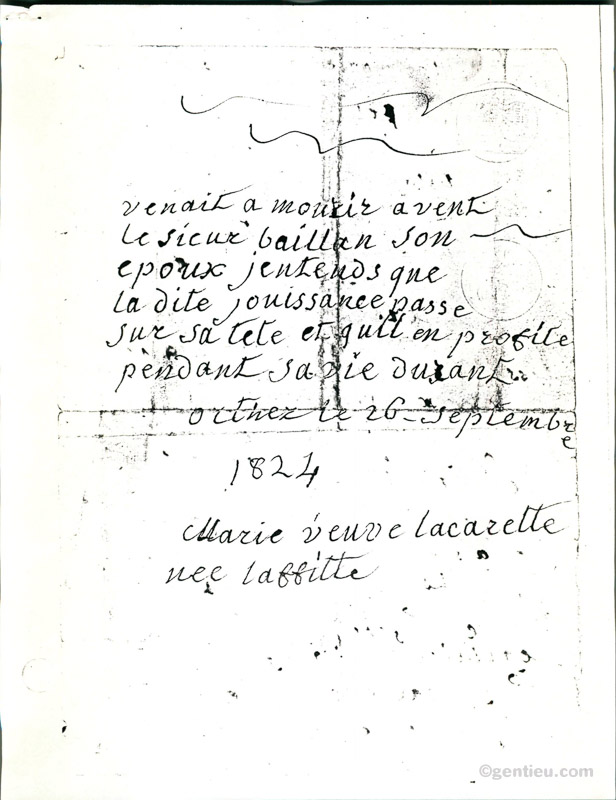

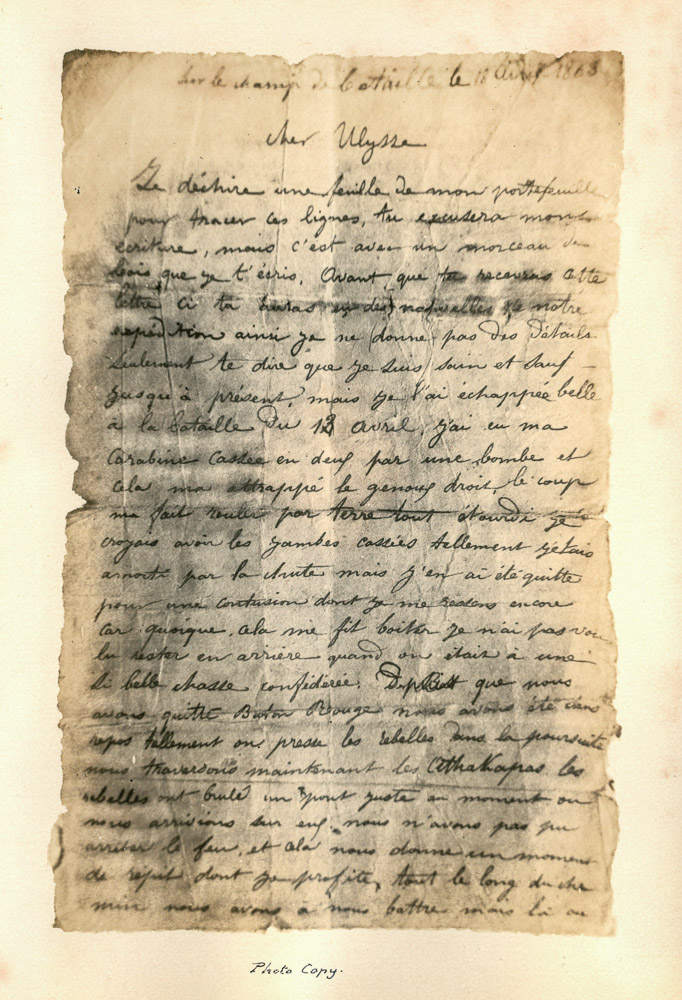

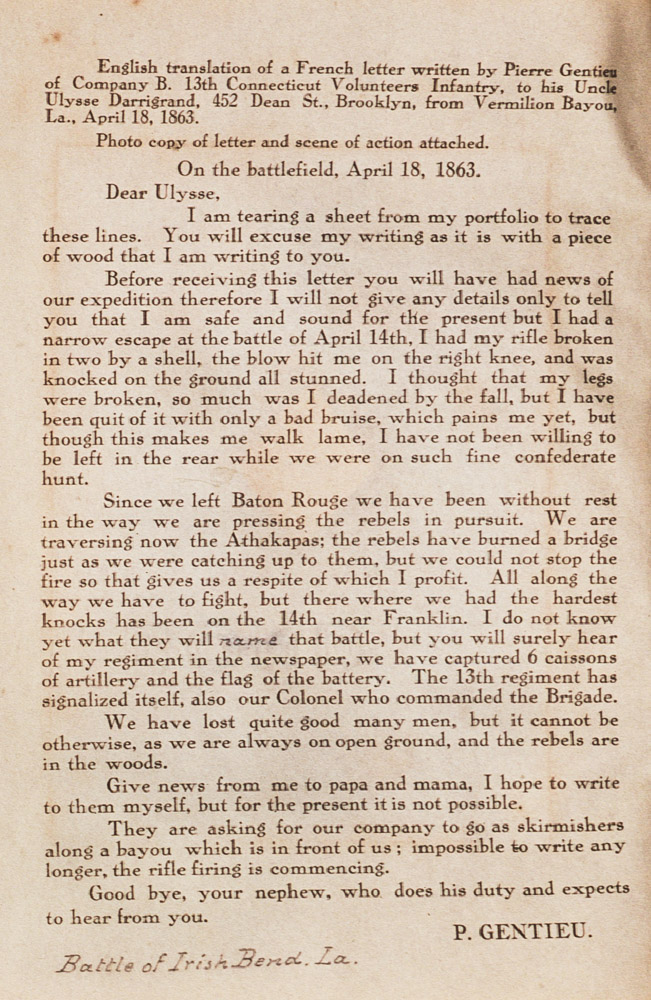

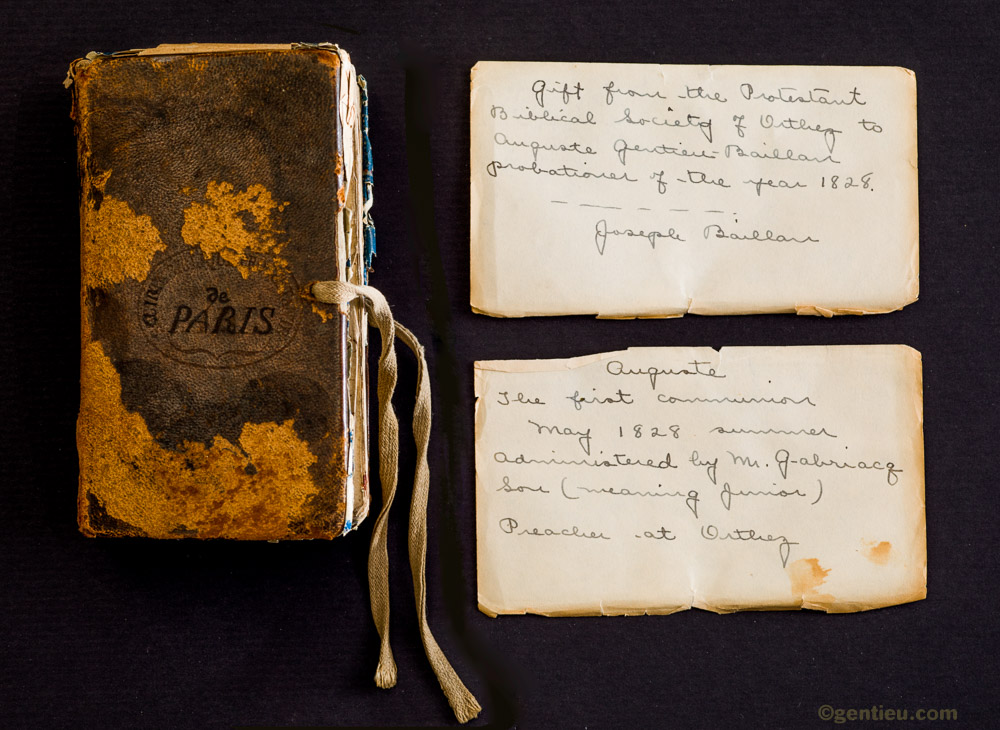

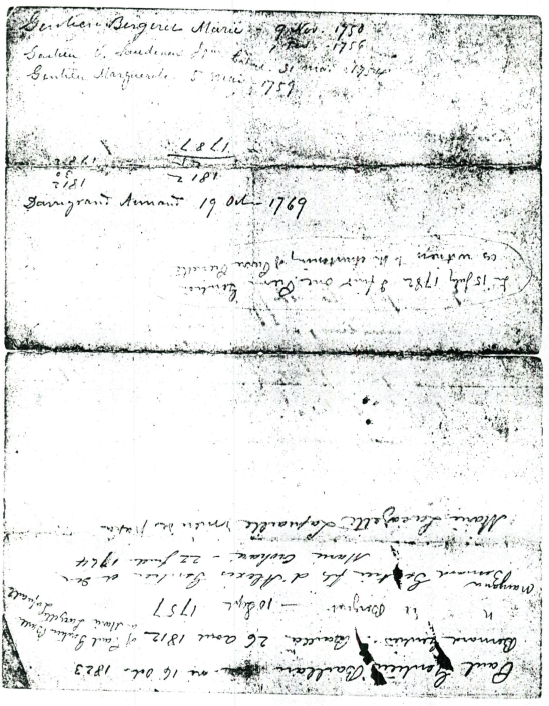

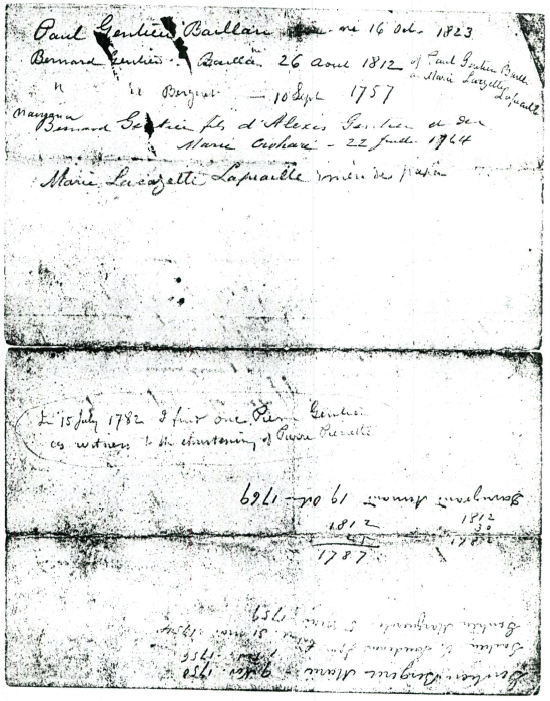

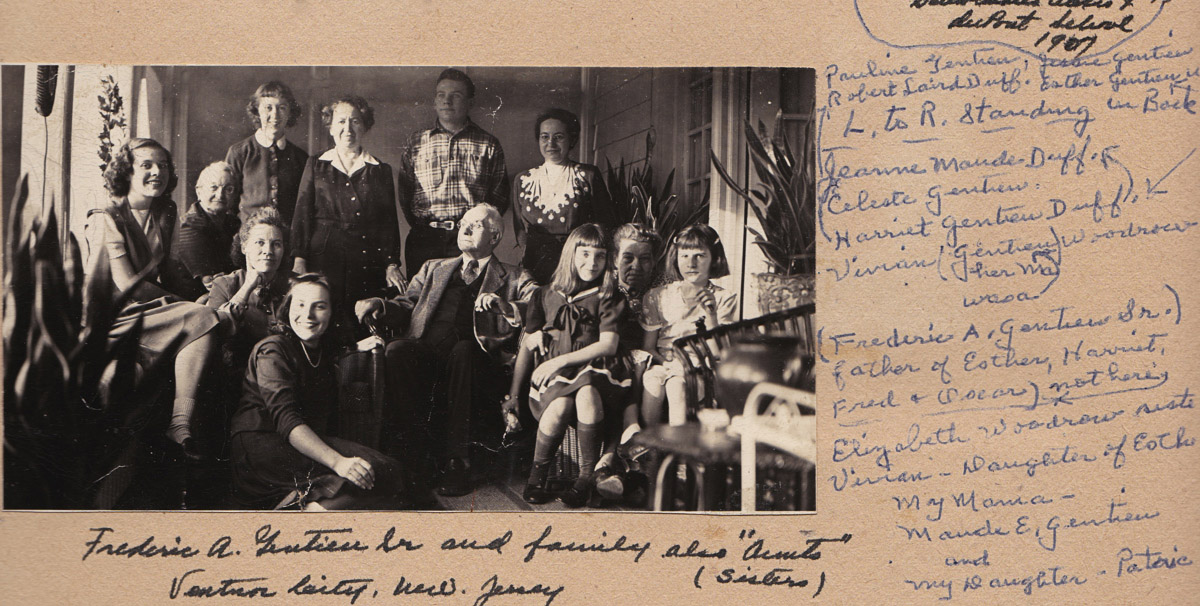

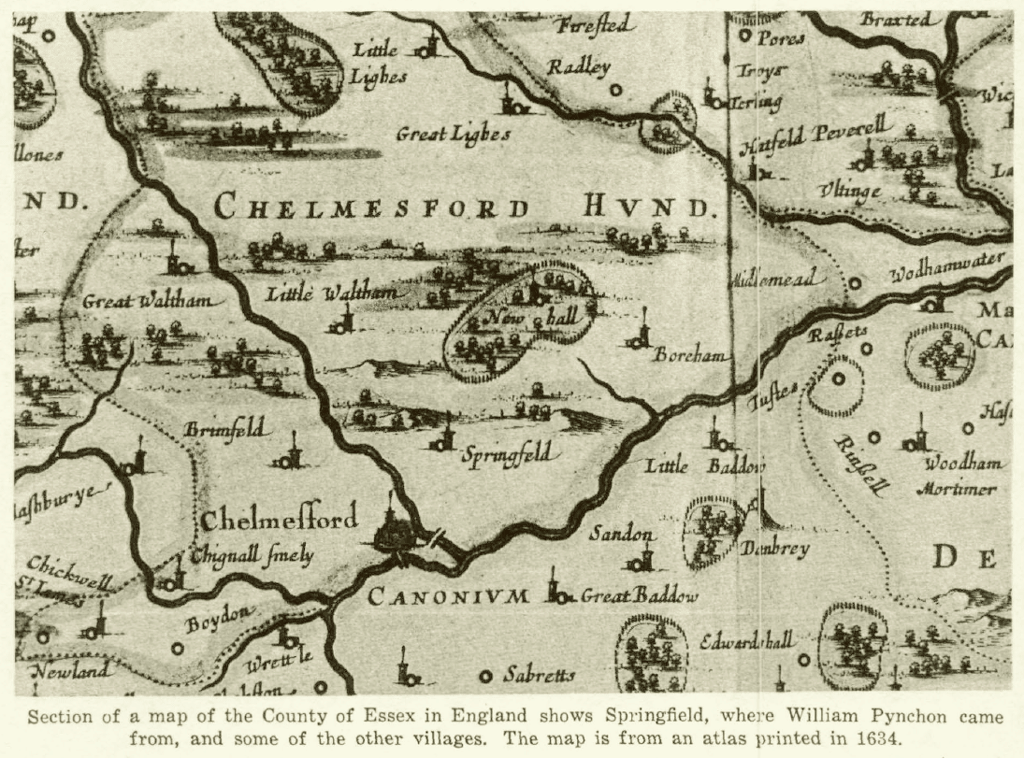

Genealogical documents showing Pierre’s connection to the Laffitte family. The first document is Pierre’s parent’s marriage contract dated 1838. Note that Pierre’s father’s mother’s name is Marie Lacazerette. The second document is Marie Lacazerette’s mother’s will dated 1824, where she signs her maiden name, Laffitte.

Perhaps the same Laffitte who owned one of the first cameras in Orthez was Pierre’s cousin, who could have inspired Pierre with an interest in photography.

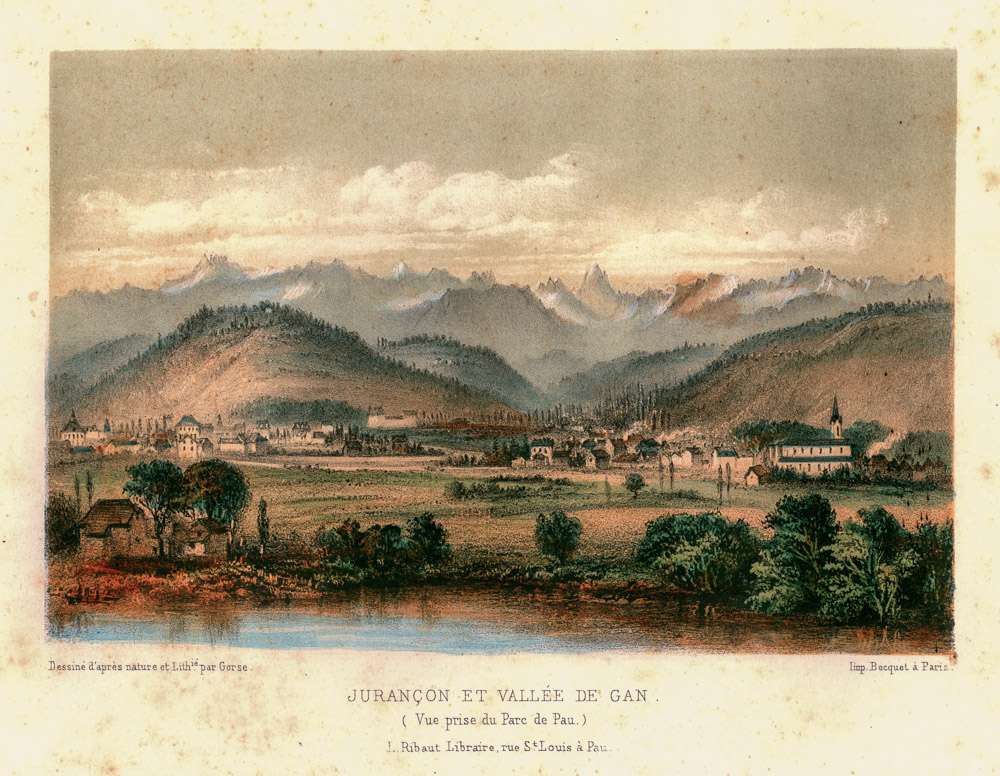

The pre-1860 photograph of the bridge

Which could explain this postcard, published by Barbe nearly 50 years later of the ancient bridge photographed before 1860, the year that Pierre went to New York. Simone had a mural of the exact photograph in an alcove of a room in her house. She told me it was taken by my ancestor. Pierre, I understood her to mean.

This is why I believe that Pierre’s photo experience began in Orthez, and that he brought his love for photography with him to America from France, and back again.