Story of a young French immigrant who came to America in 1860, what war meant to him, and the importance of his French heritage as he fathered a new American family.

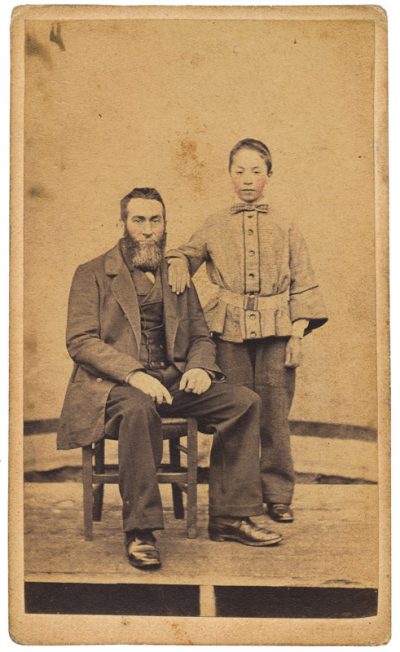

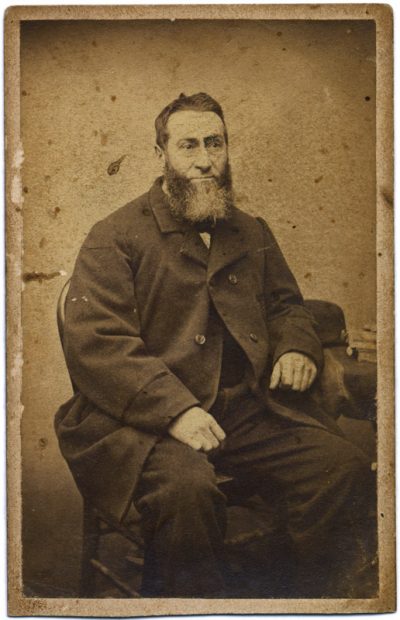

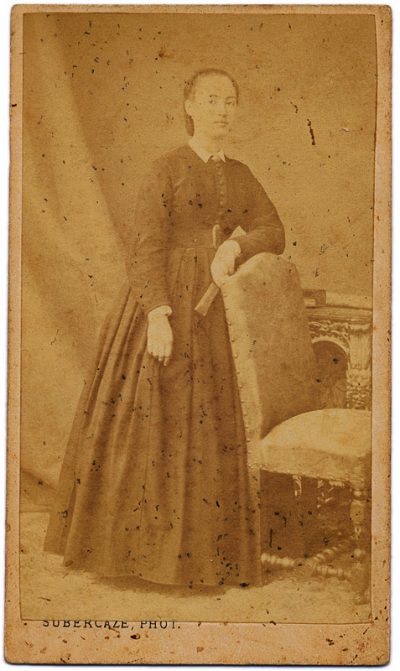

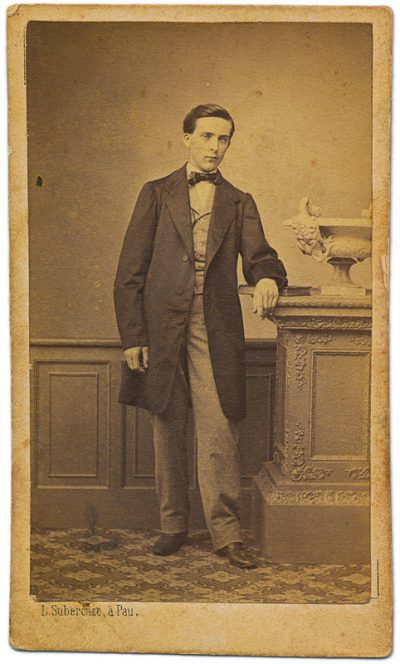

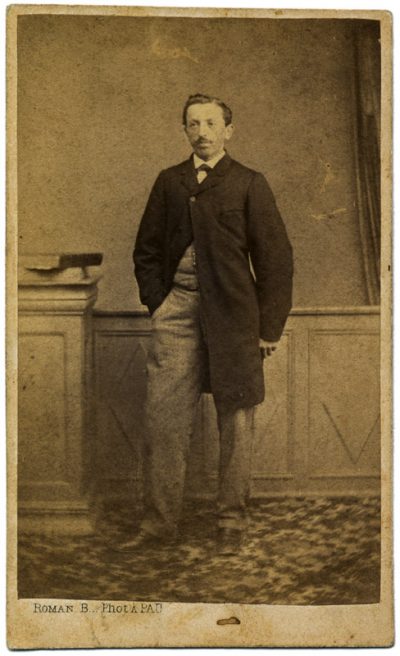

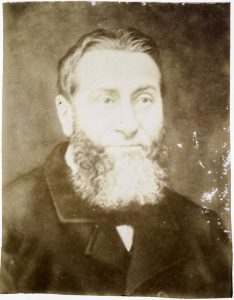

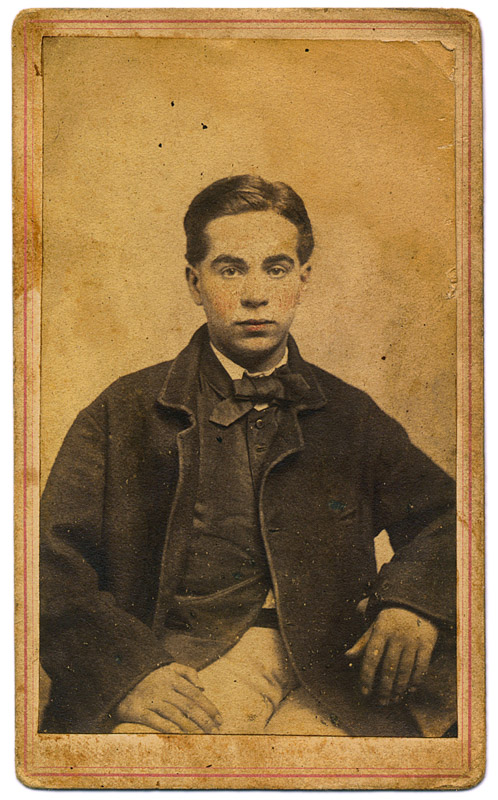

Pierre Gentieu in 1860, 18 years old

Pierre writes:

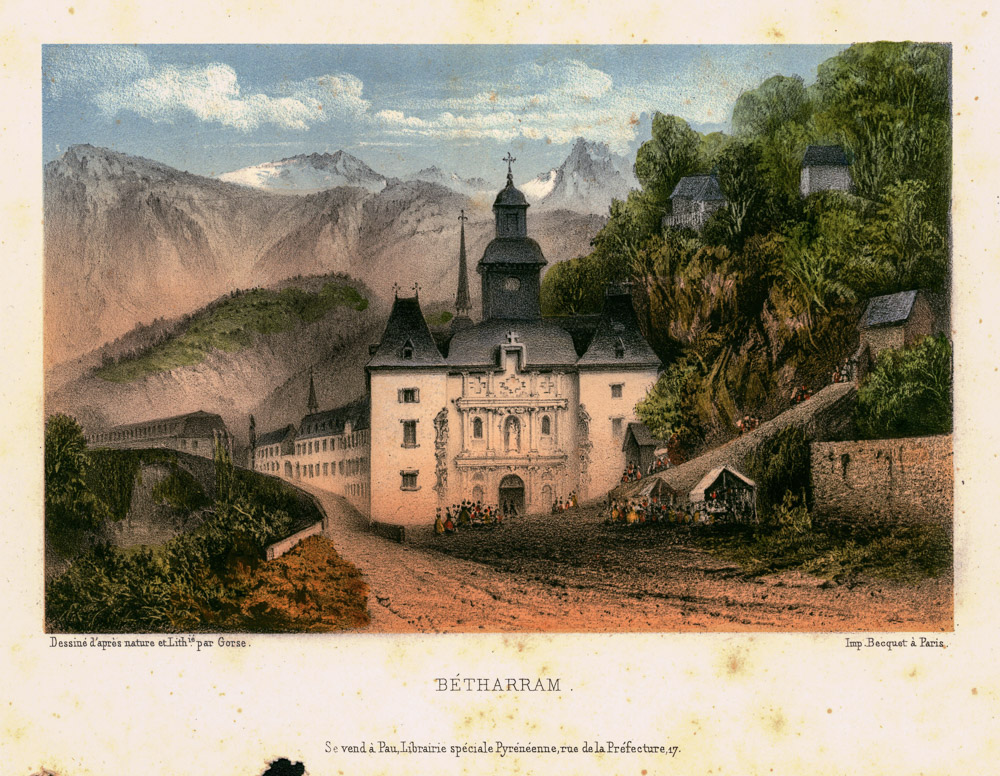

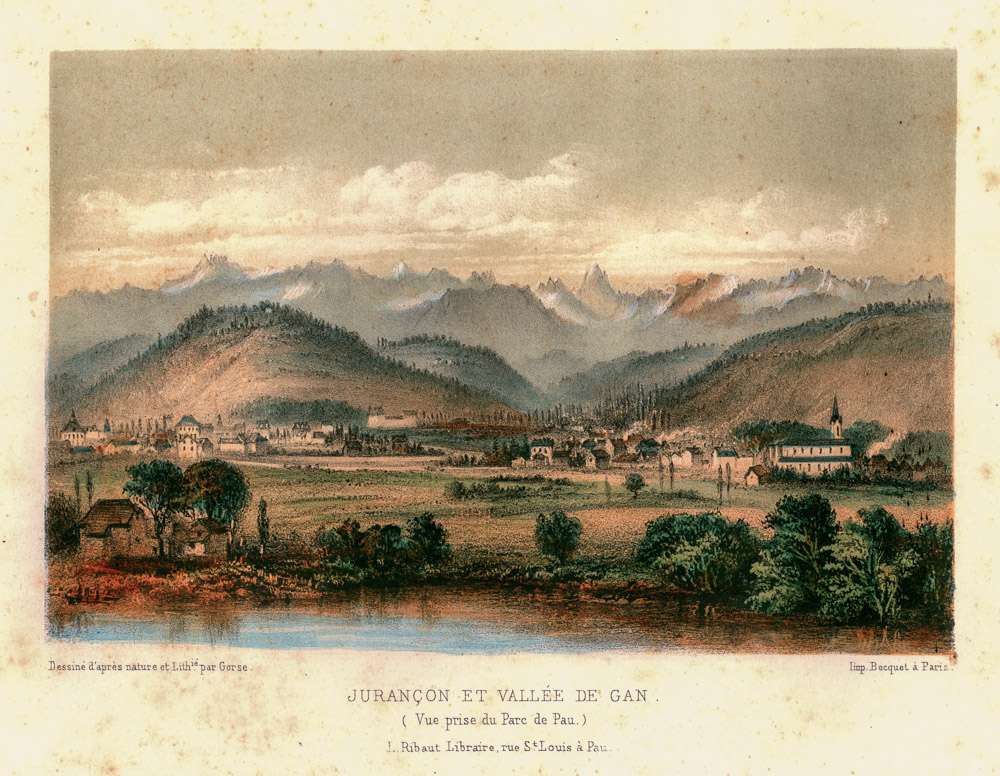

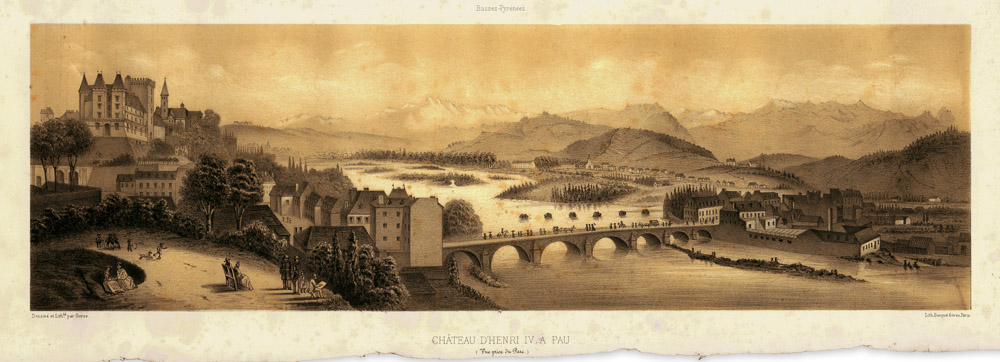

I was at the time working at the bookbinder trade in the City of Pau, and my home was in Orthez, about 40 Kilometers from there…

Napoleon 3rd. at that time issued a proclamation that all young men under age who were willing to fight for the liberty of Italy could enlist; and whatever time they would serve in that war would be deducted from their own term which they would have to serve at conscription time when of age; but all such must have the consent of father and mother, as minors, before being accepted. The excitement among the young fellows was great, and all wanted to go and fight for the liberty of Italy.

I had to write home to get the consent in due form, and telling them that all my shopmates were enlisting — would they please sign the papers at once so that we could all be in the same company. What was my surprise and disappointment when the next day I received the news that father’s and mother’s conscience did not allow them to give their consent to such enlisting. That if it had been to defend France, well and good; every Frenchman’s duty was to do so; but to go to a foreign country and maybe lose a leg or an arm in the undertaking, they would always feel sorry that they had allowed it, and consequently, I would have to wait till the regular time before going in the army. (Incidentally I would mention that two cousins were killed in that war; one at Magenta and the other at Solferino.)

Young and foolish I took offense, and told them I would then travel on my trade, what was called the tour of the country from shop to shop to perfect yourself in the trade, which was allowed by law; and as they could not keep me out of that and being afraid that I would not learn anything good on such a trip they wrote to my uncle in Brooklyn about if for advice, as I wanted to travel away from home; so Uncle answered at once saying that the best thing for them to do was to send me over while I was under age and not subject to conscription yet and could then escape the regular service when I would come of age; and being well pleased with the prospect of going to America, I was willing to accept the challenge.

On the Fourth of March, 1860 I left home, father was coming to Bordeaux to see me off on a sailing vessel. He was sad all the way, I remember, and the last words he said to me on leaving I have never forgotten. Pierre, said he, you are going very far and we may never see each other again in this world, but surely live a Christian life, so that at last we may all meet together in heaven.

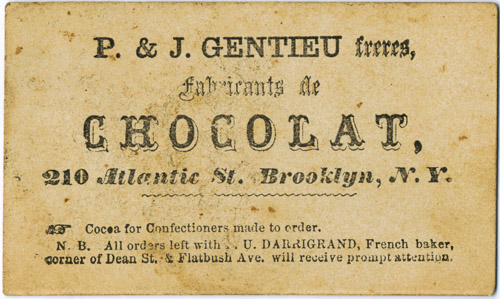

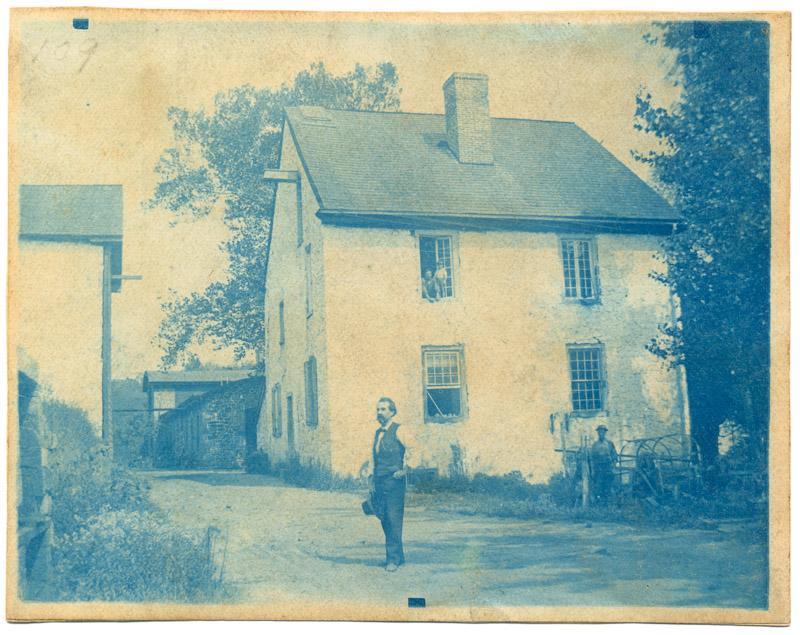

Pierre's aunt and uncle, the Darrigrands, and their French bakery on Dean Street in Brooklyn, where Pierre first lived in America.

He stayed with the Darrigrands in Brooklyn, N.Y. until the severity of the winter drove him South to New Orleans, La. in search of a warmer climate. He was in La. when the Civil War started, a member of the New Orleans Artillery and the Louisiana State Militia. When these State troops were called into the Confederate service, the soldiers were given an opportunity by their colonel, just before leaving the State, to leave the regiment if they did not wish to go. Being a native of liberty-loving France, he could not become reconciled to the cause of slavery, end consequently was first of about thirty-five men to step out of line. Jessie Gentieu family history, 1939

“I would state that the reading of ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin’ in the old country influenced me first against slavery. The story was published as a serial in the daily papers; and I remember how intent we were in the evening to hear our father read each installment, and all the remarks we were making about it, how it was possible that the country boasting of being ‘the land of the free and the home of the brave’ could legalize such an institution, when in France, which was not then a republic, would not tolerate such a thing; for to us children, all the people before God were equal, and the color of the skin had nothing to do with it; but it was only the degree of instruction and civilization that made the difference in people.”

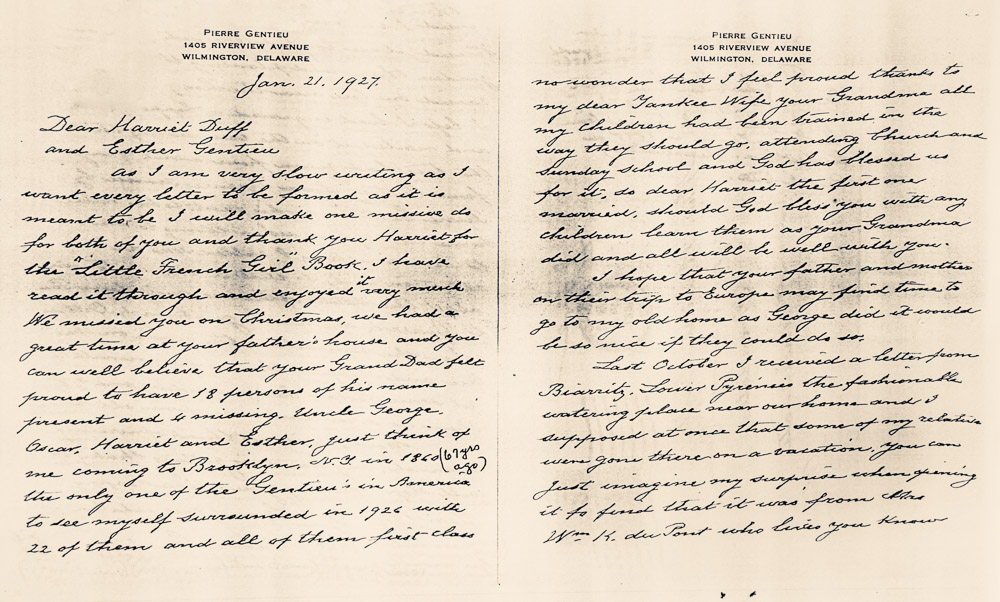

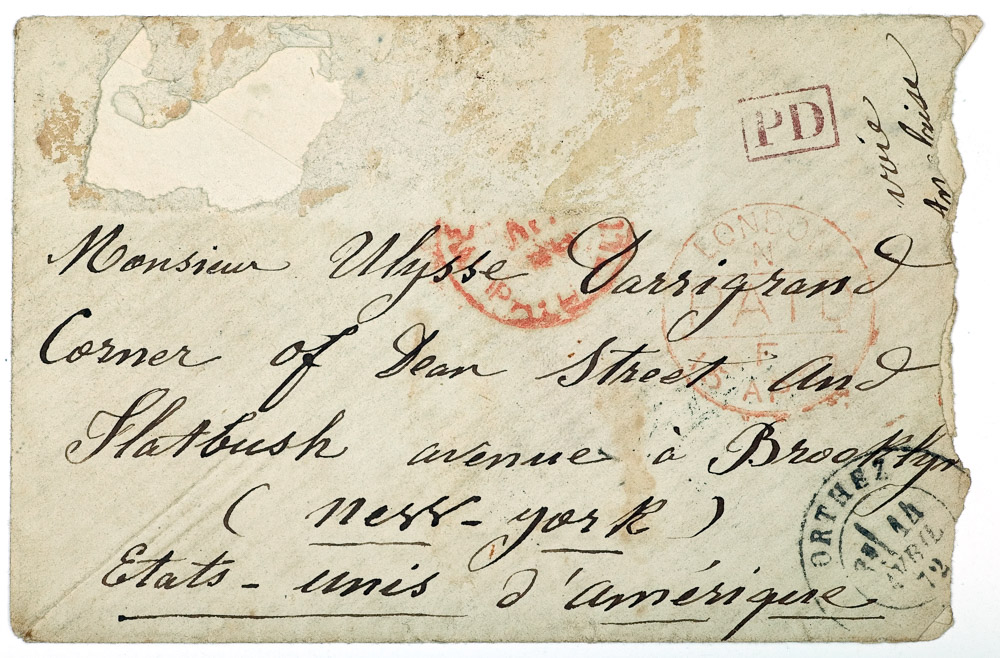

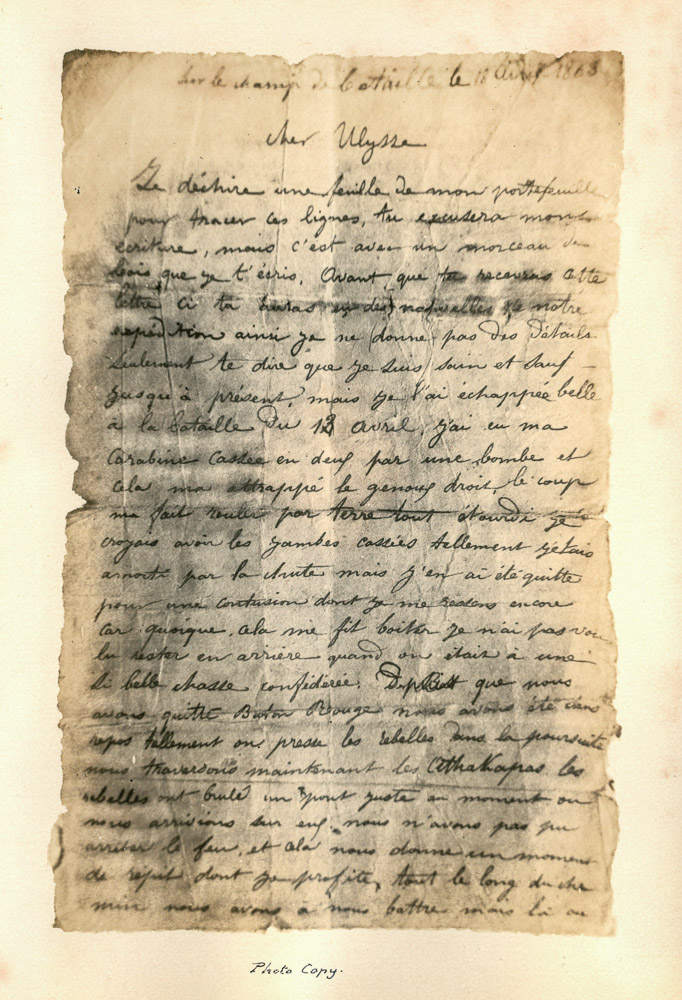

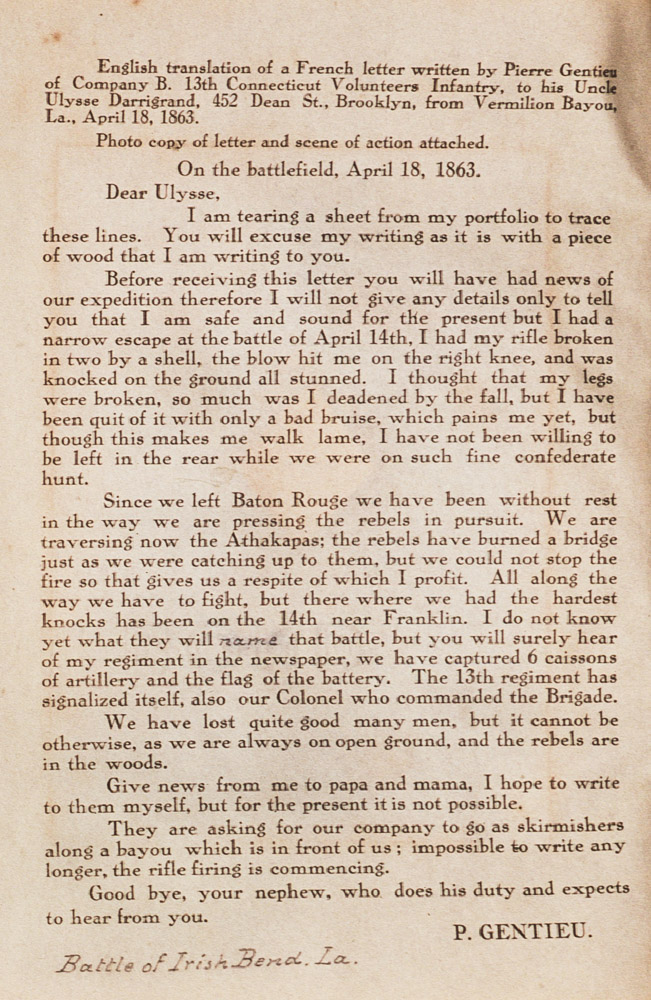

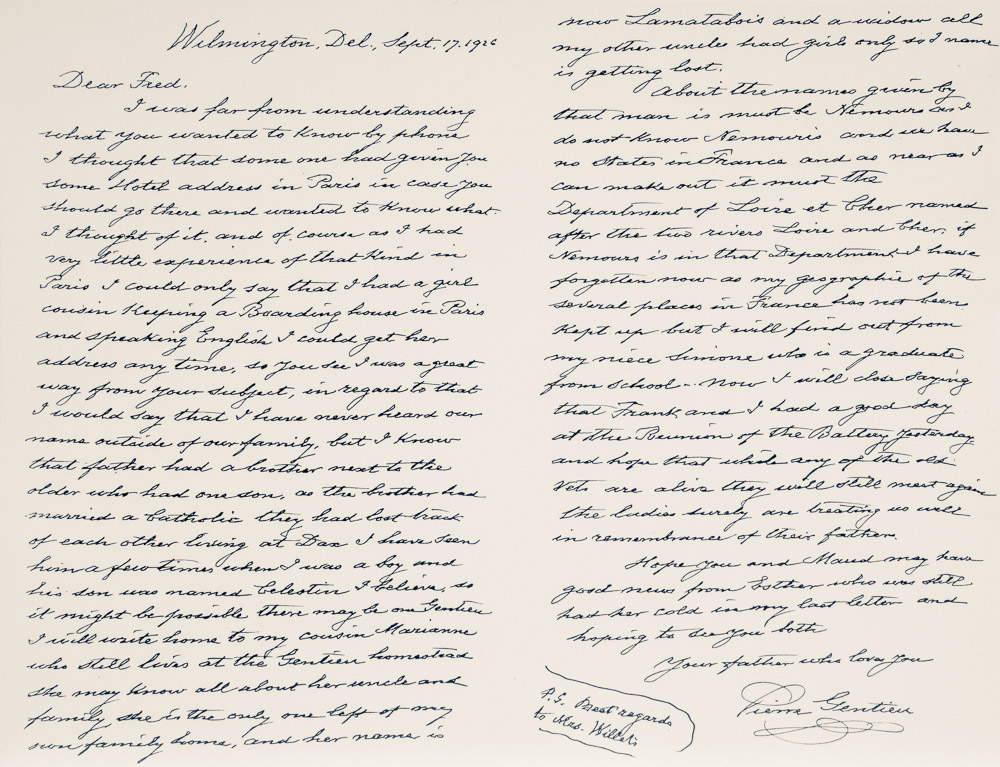

Pierre’s letter from the battlefield to his uncle Darrigrand

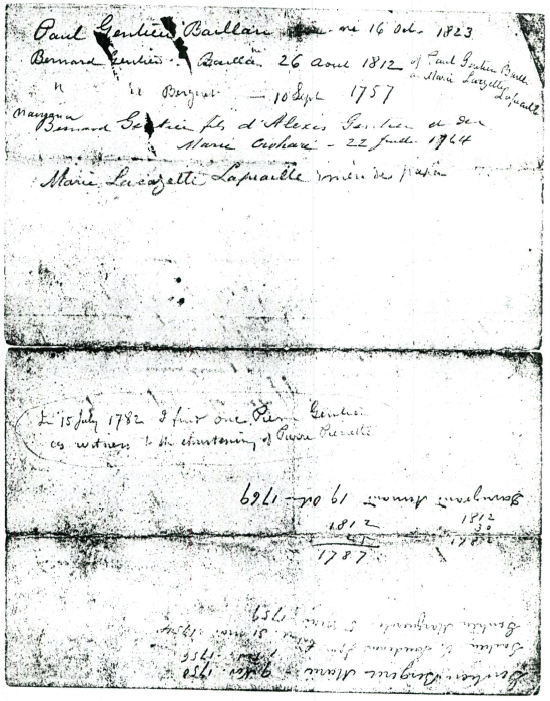

Regarding the Gentieu-Baillan name

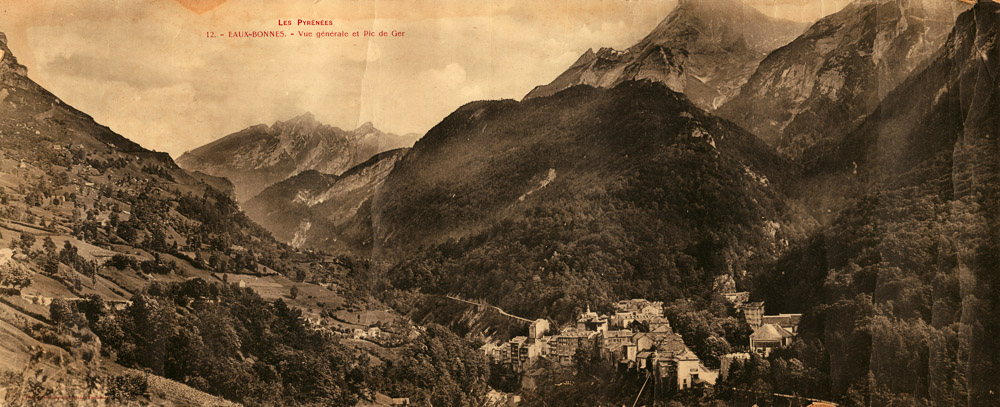

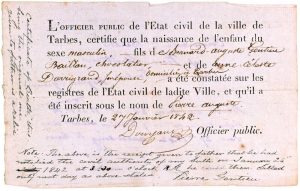

Full name of the family in France, is Gentieu-Baillan, the last having been added through marriage. The home place is Orthez, Lower or Basses Pyrenees, France - have kept only the name of Gentieu, as being the real family one, both not necessary and shorter in use. My full name otherwise is Pierre Auguste Gentieu-Baillan, shortened to Pierre Gentieu. Born at Tarbes, Hautes or Higher Pyrenees, France on January 26, 1842 during a temporary absence from Orthez by father and mother on a call to his brother who was sick. Taken from record in the family Holy Bible written in Pierre Gentieu’s own hand-writing

The addition of the name of Baillan to the family name of Gentieu was explained verbally by Pierre Gentieu thus: "A girl by the name of Baillan was the last of her family, and rather than have her family name die out, she requested when she married a Gentieu, that her name be added to his, and continued thru the years." This was done in France, and was continued in the U.S.A. by Pierre Gentieu until he enlisted in the Civil War. When the man who signed him up during the war asked him his name, he said, "Pierre Auguste Gentieu-Baillan." Then the man in charge repeated that he wanted his name, and not his pedigree, he replied, "Pierre Gentieu". Jessie Gentieu family history 1939

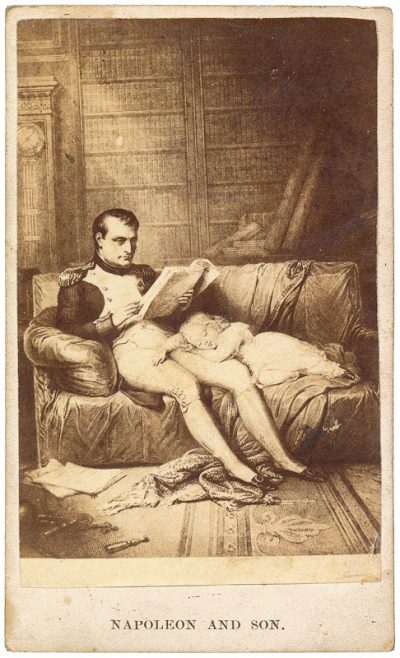

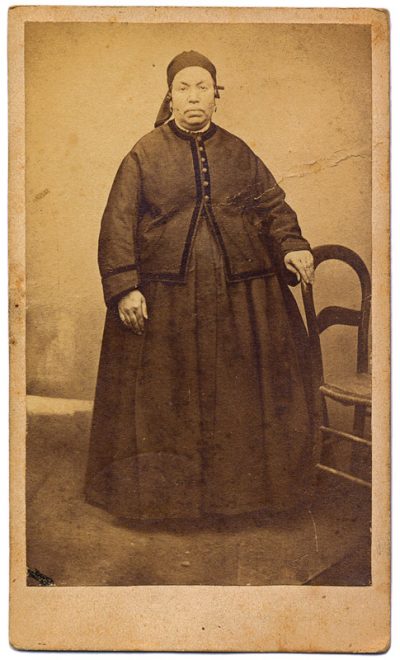

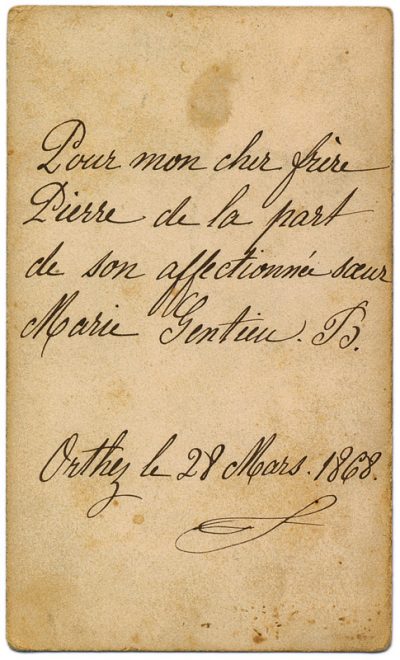

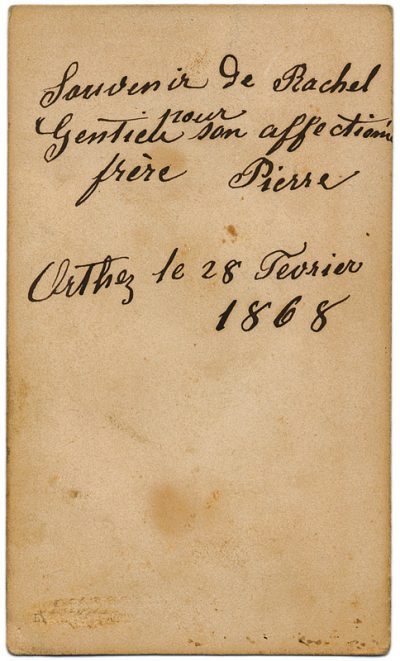

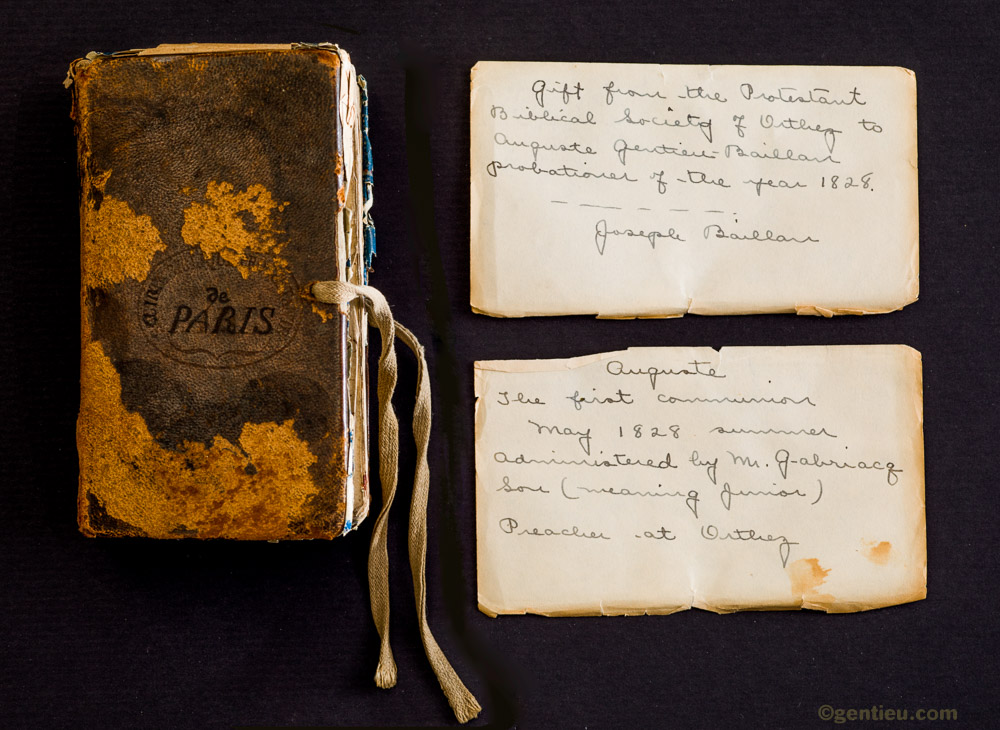

Pierre’s carte de visite album

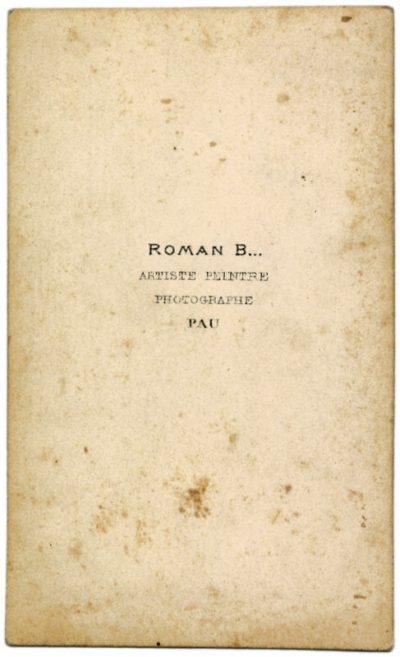

Pierre prized his father’s French Holy Bible

Pierre’s professions

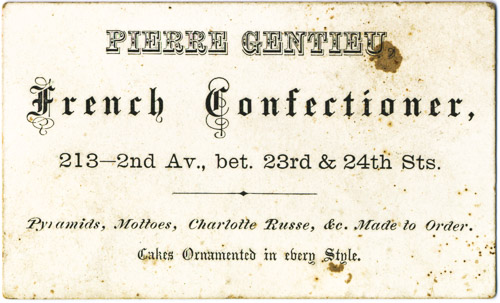

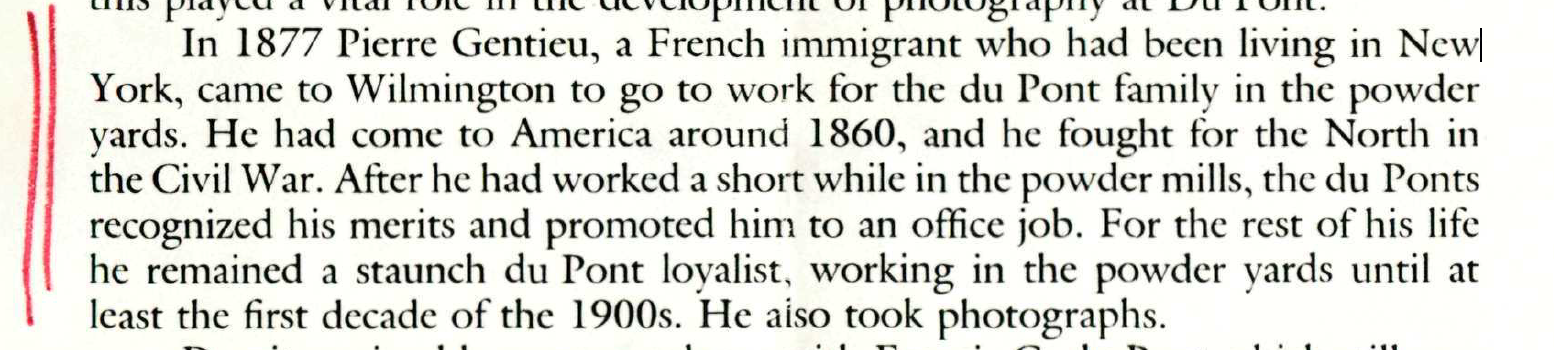

After the Civil War, Pierre had a chocolate shop in Brooklyn with his younger brother, Joseph, and a French confectionary shop in New York. Joseph came to live in America in 1861, one year after Pierre arrived.

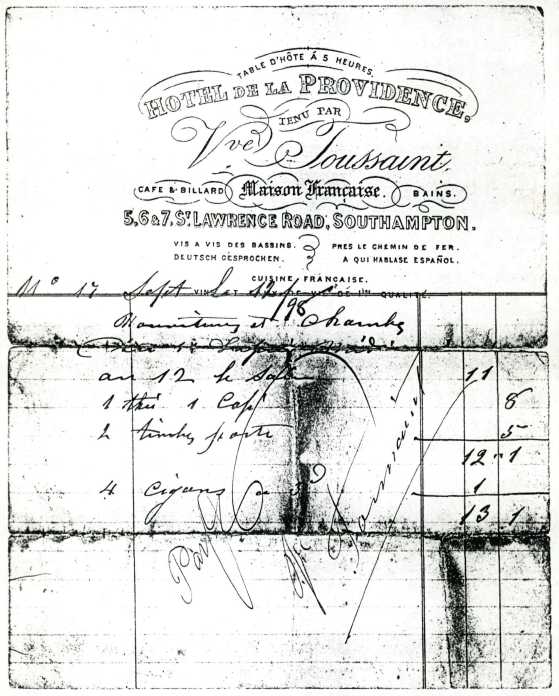

Pierre’s 1898 trip to Orthez

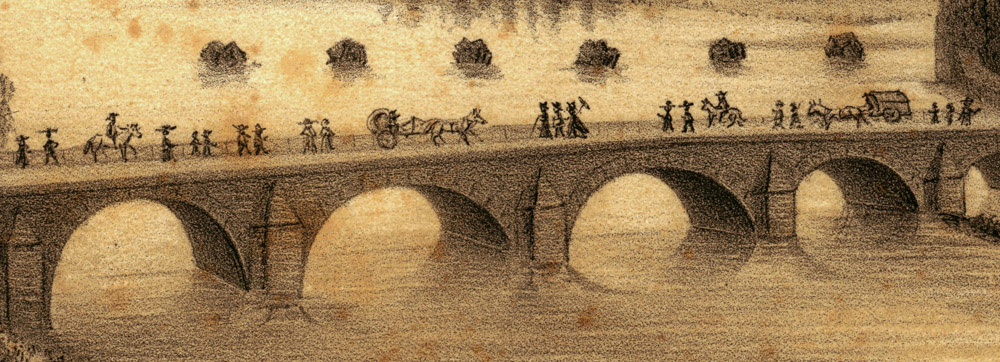

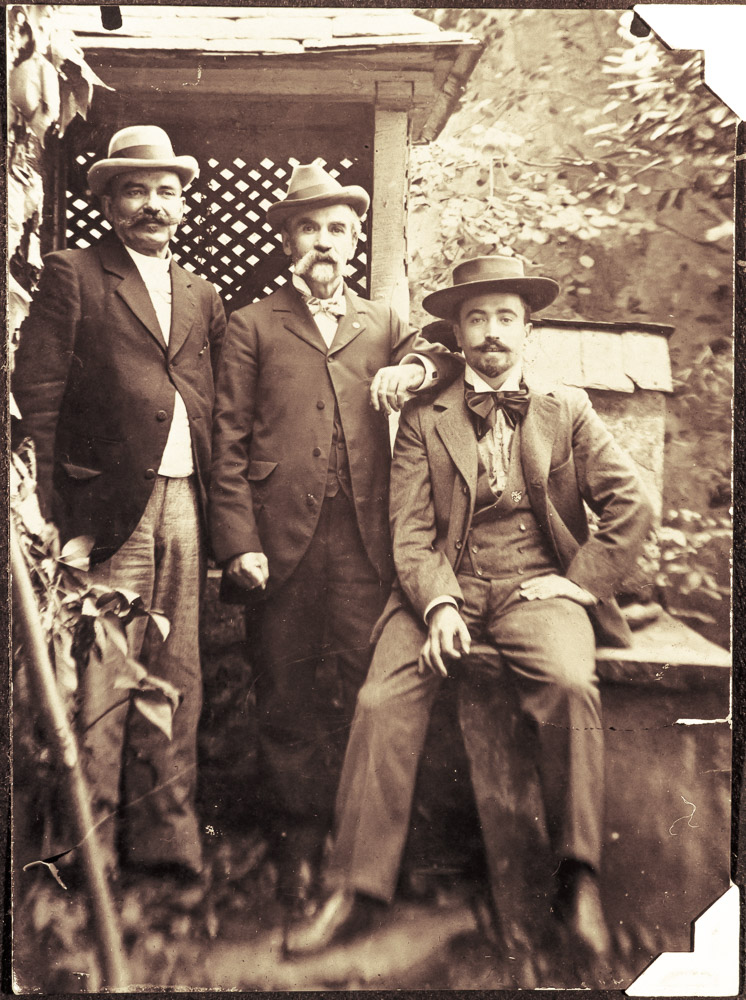

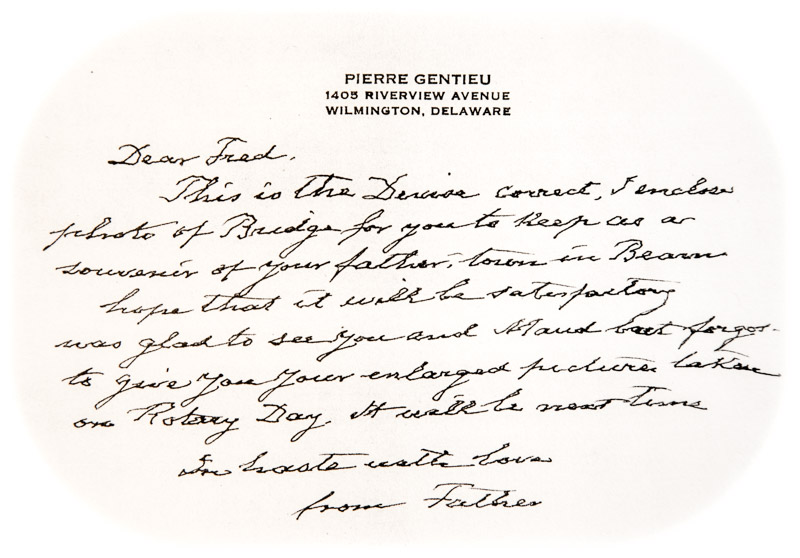

Photos that Pierre made during his visit to Orthez in 1898. The ancient bridge, the Gentieu-Baillan chocolate shop, Pierre (center) with his brother-in-law Germain, and nephew Auguste Pondarre.

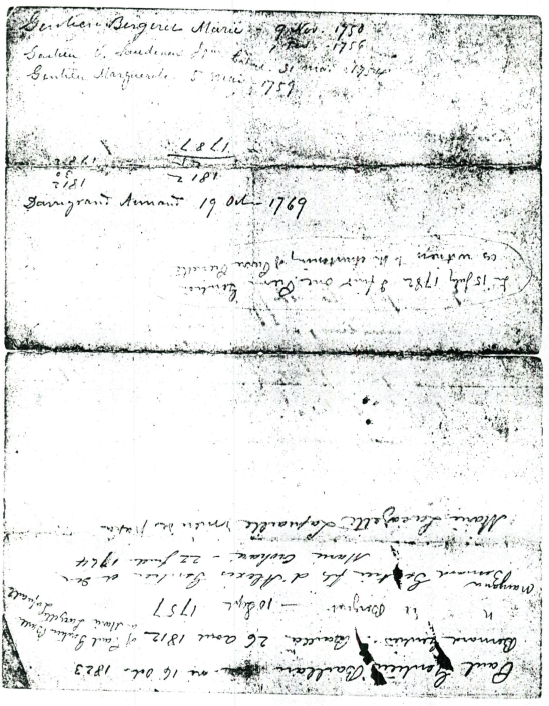

During the summer of 1898, Pierre Gentieu made a return trip to France, and looked over old family records in the Town Hall. Among his papers are listed these names - Bergerie Marie Gentieu, Nov.9,1750, V. Saudenerx Gentieu, Nov.1,1756 - Marguerite Gentieu, May 5,1759, Maryana Bernard Gentieu, son of Alexis Gentieu and Marie Crohare, July 22, 1764. There is also written, “In 15 July l782, I find one Pierre Gentieu as witness to the christening of Pierre Pierrette.” The balance of the records were destroyed during the French Revolution, so the family tree is incomplete. Jessie Gentieu family history 1939

Pierre's contemporaneous research notes made while in Orthez in 1898.

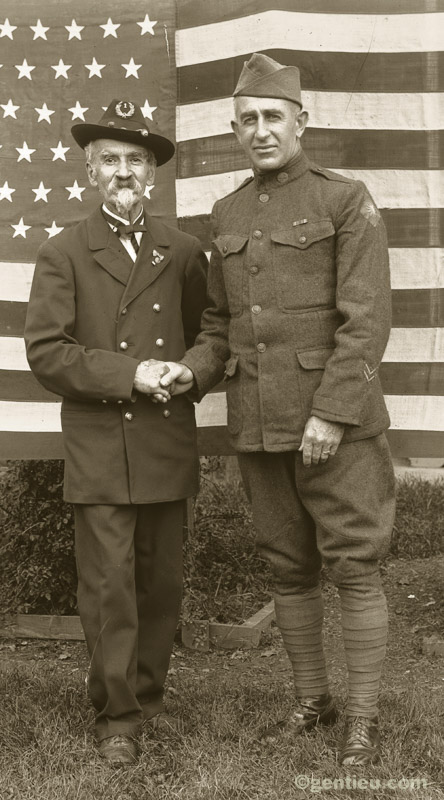

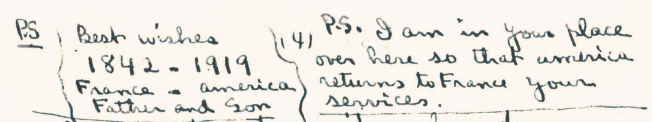

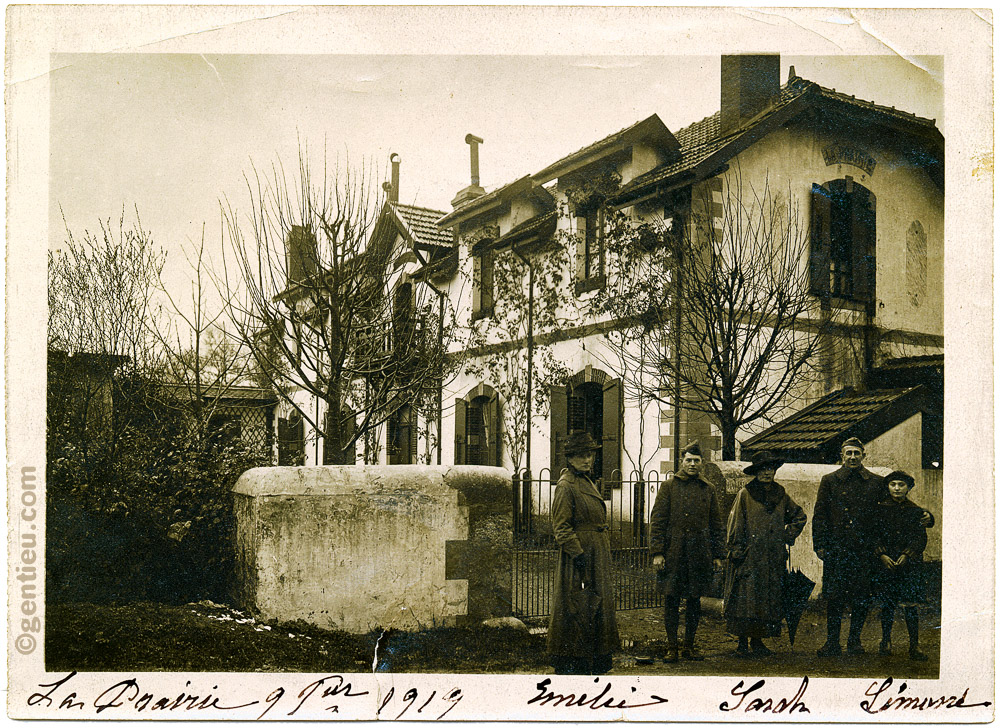

World War 1: Pierre’s son George in France. “I am in your place over here so that America returns to France your services.”

Pierre's son George served in France in World War 1 and visited Orthez three times. Row 1, Pierre with George; George's cousin, Auguste Pondarre who served in the French Army; George with comrade and Auguste. Row 2, P.S. in George’s January 5, 1919 letter to Pierre from where he was stationed at St. Nazaire, France

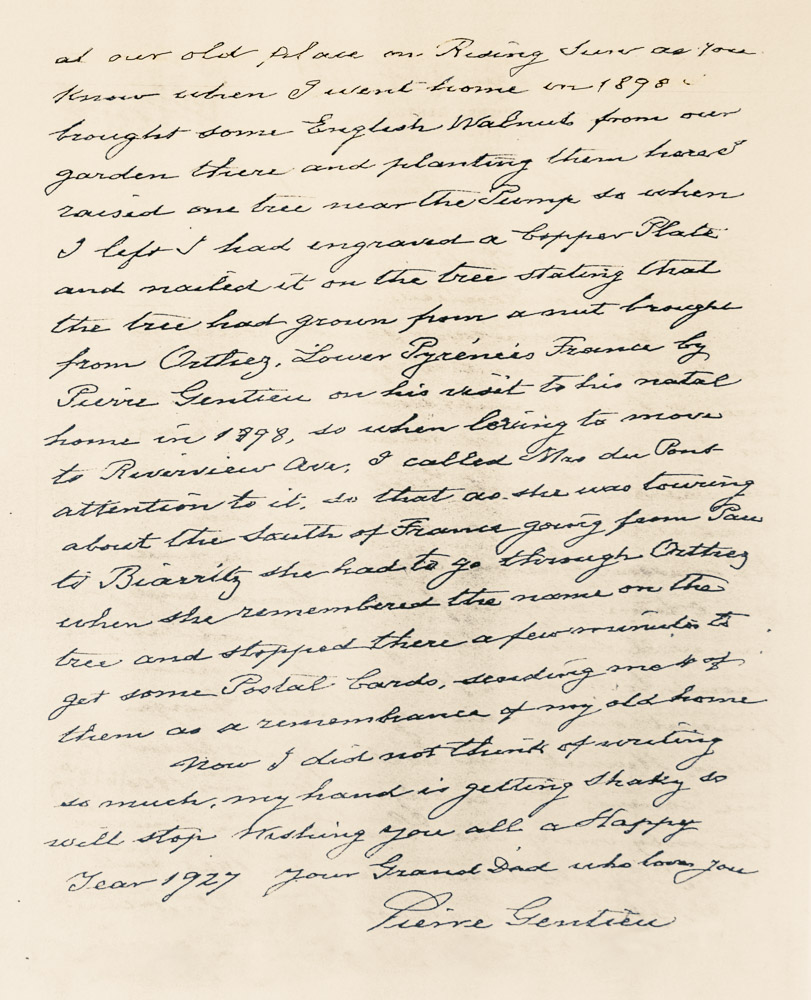

From a French English Walnut seed, an American family tree grew

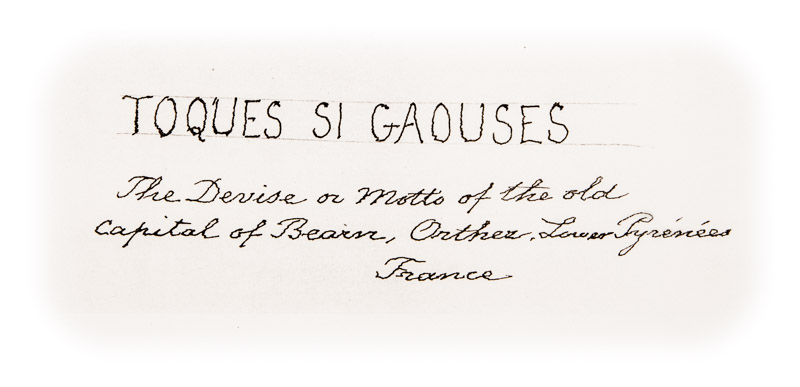

Gentieu family motto taken from the motto of the old Capital of Bearn, Orthez, Lower Pyrénées, France

The basis of the Gentieu motto "Touquoy si Gaoses," meaning "Touch It If You Dare" as shown on the family Coat of Arms was taken from an old bridge bearing that inscription at the entrance of Orthez. "Touquoy si Gaoses" is not strictly French, but a Bearnaise language spoken only by a small group of people inhabiting one of the Southern Provinces of France. In the Gentieu home in Orthez there wan a maid who spoke that language. She could understand the Gentieu French, but they could not understand her Bearnaise, so in making the Coat of Arms, Pierre decided to use the Bearnaise, rather than the French, thinking it would be more distinctive, and something no one else could read. He succeeded. Jessie Gentieu history 1939

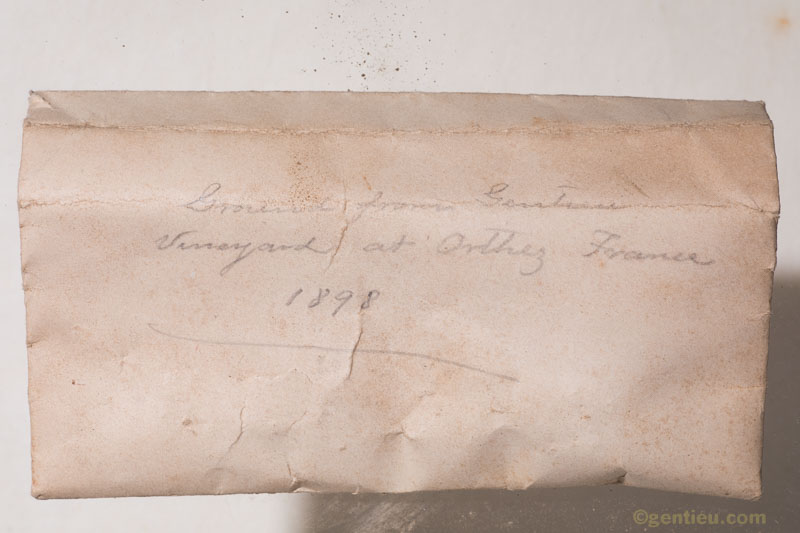

Ground from Gentieu Vineyard at Orthez, France 1898